Theatre

ReadReview: Cirque Du Soleil’s Corteo

Cirque du Soleil’s timeless appeal lies in its lavish attention to detail and slick spectacle.

Books & Poetry

ReadThe soft and quiet power of Australian literature needs public champions

Following the abrupt closure of Australian literary journal Meanjin after 85 years, Splinter journal editor Farrin Foster reflects on how literature’s quiet power makes it one of our least-valued art forms.

Books & Poetry

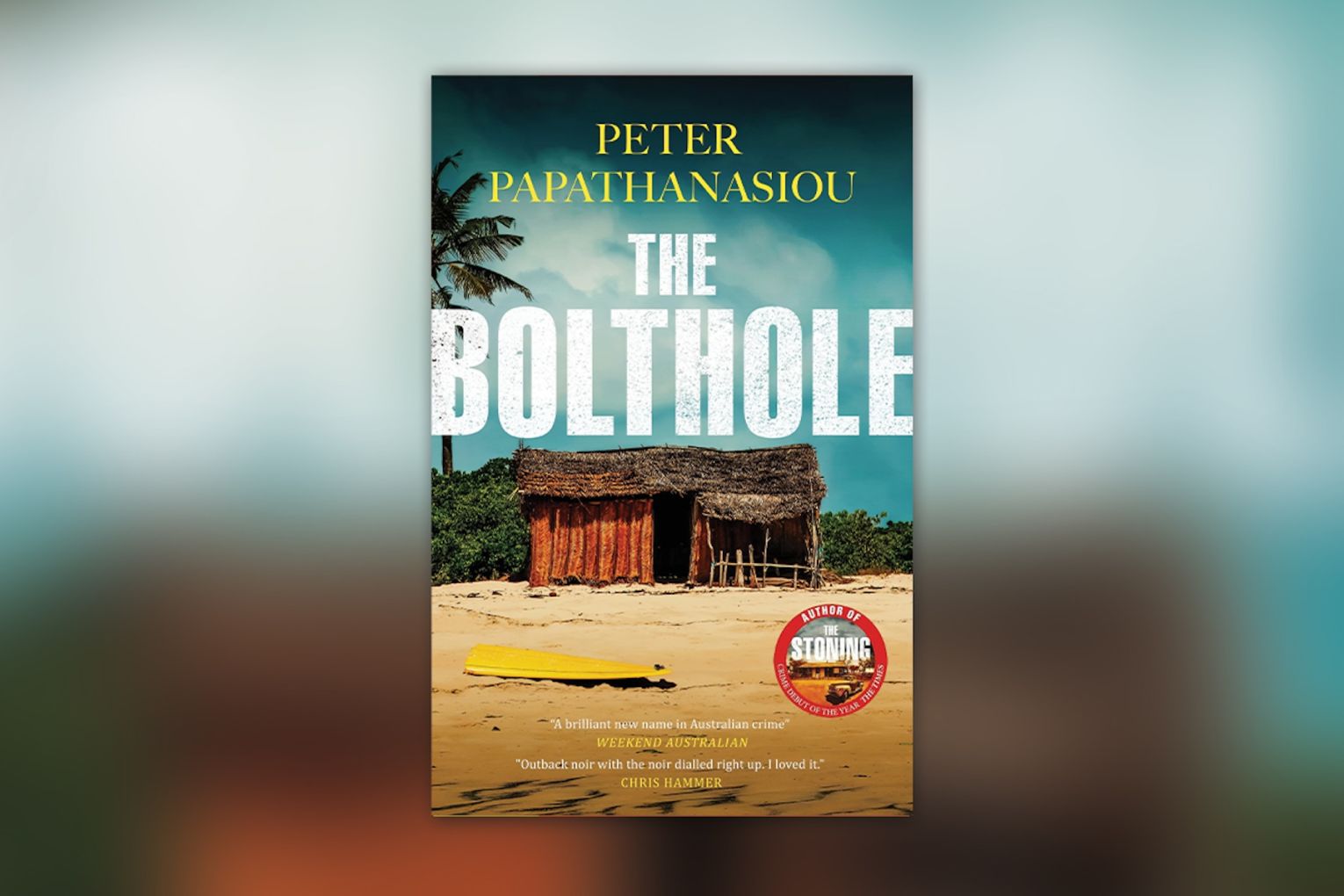

ReadBook review: The Bolthole

Author Peter Papathanasiou embraces Kangaroo Island for the latest in his George Manolis detective series, where the machinations of the small community machinations are as compelling as the murder mystery.