Theatre

ReadState Theatre Company South Australia promises shorter runtimes and ‘meaty, nuggety questions’ in 2026 season

Recently appointed State Theatre Company artistic director Petra Kalive says her first program meets the challenges of an aging audience and an “increasingly AI and online” world. The company’s 2026 slate includes a tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsburg alongside experimental local work – including an ASMR-inclusive take on Uncle Vanya.

Books & Poetry

ReadThe soft and quiet power of Australian literature needs public champions

Following the abrupt closure of Australian literary journal Meanjin after 85 years, Splinter journal editor Farrin Foster reflects on how literature’s quiet power makes it one of our least-valued art forms.

Books & Poetry

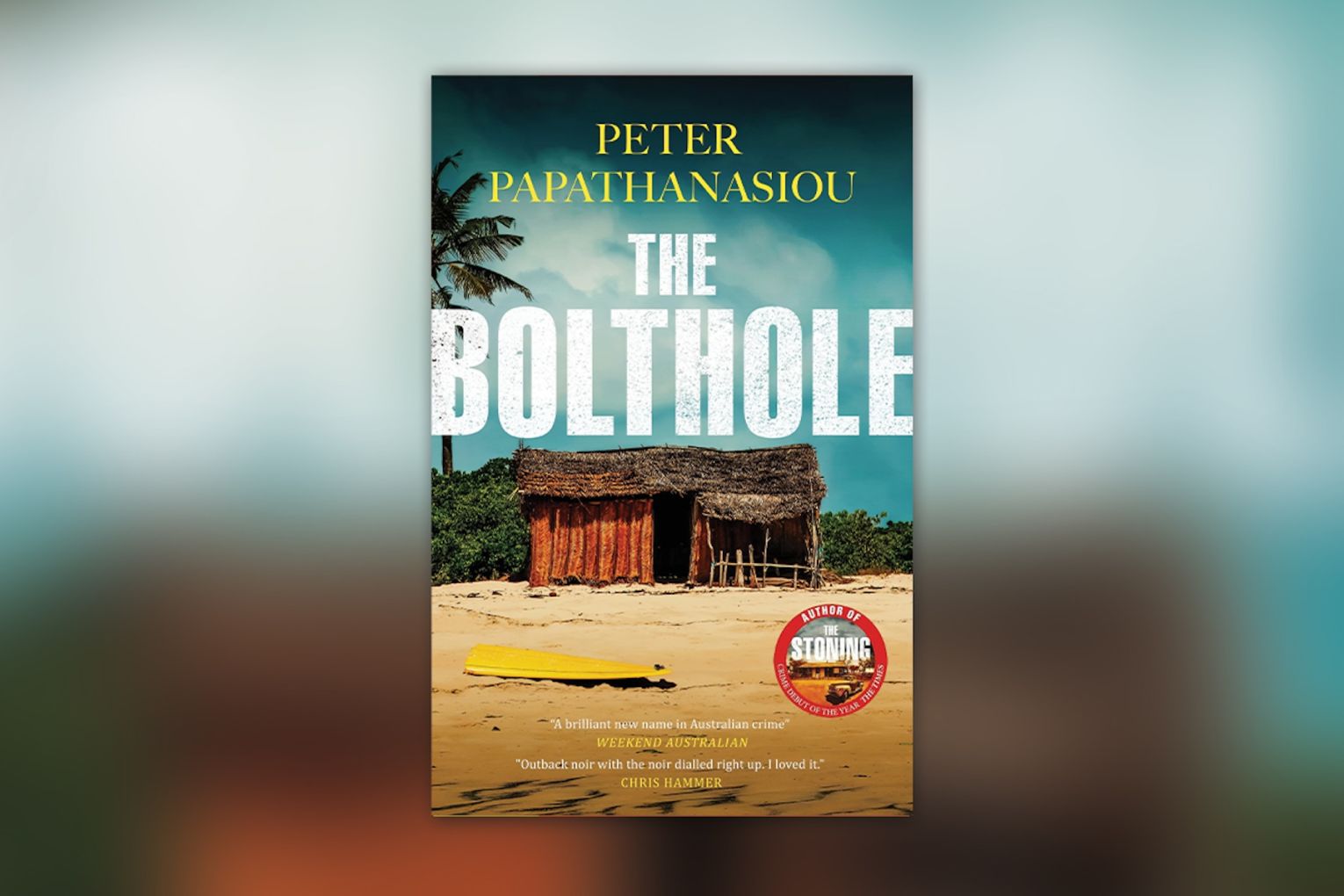

ReadBook review: The Bolthole

Author Peter Papathanasiou embraces Kangaroo Island for the latest in his George Manolis detective series, where the machinations of the small community machinations are as compelling as the murder mystery.