Our libraries need more, not less, money

Books & Poetry

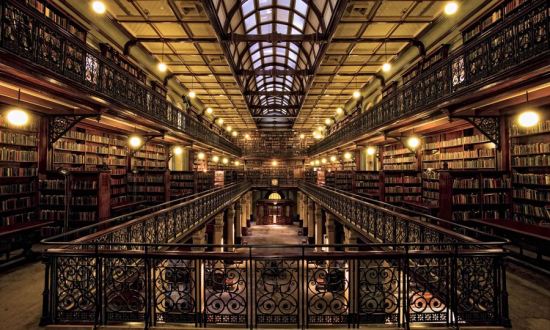

The State Library of South Australia is a treasure offering knowledge, pleasure, a window to enlightenment – all of which are threatened when libraries become a soft target for government cost-cutting, writes author Stephen Orr.

After the fall of Juan Peron in 1955, author Jorge Luis Borges, almost blind, but still perhaps the most visionary writer of his times, was made director of the National Library in Buenos Aires. According to his biographer, Edwin Williamson, he then sponsored “several measures intended to overcome what he saw as the narrow-minded philistinism of the Peronist regime”.

He set about expanding a neglected collection, revived the library’s journal (La Biblioteca) and devised a lecture series for speakers “committed to the cause of intellectual freedom”.

Although Borges was losing his sight, he could still see the importance of words, ideas and information, and realised that democracy, freedom to think, to aspire, imagine, question, all came at a price. Financially, of course (and here I should invoke the point of my letter: that is, the Weatherill Government’s attempt to strip our own State Library of funds, staff and, ultimately, resources); but also, the will, the determination to make books (and the 23 letters that fill them) the centre of a culture, or at least an important part of it.

Fourteen years before his appointment, in his story collection The Garden of Forking Paths, Borges described the Library of Babel, where “all men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal problem, no world problem, whose eloquent solution did not exist.”

And it’s this treasure I’d like to discuss.

What do we see when we visit the State Library of South Australia? Individuals, mostly, plucked from the “real” world (although Borges saw it the other way round) for a few hours. Investigating the library’s fine collection of family history documents, or investigating a trove of history texts, images, biographies.

It’s a past our elected leaders sometimes seem intent upon forgetting. Cultural amnesia. Why? Maybe they don’t actually read themselves (surely not!); maybe they find certain objective truths unpalatable; or, as I suspect, maybe they don’t see the importance of thought-out words organised into paragraphs, chapters.

On each visit I see university students in their glassed-in rooms, old men reading about the heroic deeds of their grandfathers (and him, that man, homeless perhaps, but warm for a while, reading a newspaper, or a journal about the job he used to have, in the days when they also seemed important).

But more, as in the Library of Babel, there is hope “that the fundamental mysteries of mankind…might be revealed”. There seems plenty of evidence of this (that girl, there, studying a book about inorganic chemistry – although, soon, there might not be money for the book, the librarian, the lighting, the library itself).

The State Library has been asked to find $6 million in savings over three years. This equates to 20 of its 115 full-time positions.

It seems hard to understand. As if there are 20 people sitting around with nothing to do. Not my experience, or understanding. At which point Jack Snelling’s Arts SA finds someone to tell us this new cheaper, leaner library will ensure “structural and financial stability…while still being able to deliver on its strategic plan”.

Ah, the plan! “Every chance for every child – giving our children every chance to achieve their potential in life”. A public service sentence, but regardless, the same plan that saw another 12 jobs cut from the library in 2015; that has marked libraries as soft targets (despite 9 million people using them nationally every month). As elsewhere. Western Australia’s Barnett government saved $1.7 million last year by cutting inter-library loans (despite the fact that 355,000 books were exchanged in WA in 2015). All part of the new knowledge economy, apparently.

Why does this worry me?

For a start, writers earn money from libraries. Fiction pays very few bills. Increasingly, authors’ incomes derive from the Copyright Agency, a federal organisation that surveys libraries, uses samples to judge the number of books authors have in public libraries, and pays a corresponding fee. This adds up, but requires sampling, people to fill in paperwork, do the bureaucratic hard yards.

Libraries organise and host author talks; come up with, and implement, schemes such as the National Year of Reading; children are entertained; migrants helped (for example, the State Library’s excellent English Language Learning Improvement Service).

And so it goes. Hardly expensive, for the knowledge, the enlightenment, the pleasure provided.

But increasingly, writers and readers are meant to justify their existence (like a dog waiting beside the dinner table for a few scraps), start online petitions, write letters to their members (like mine, always unanswered).

All the time, the decay. All the time, a Premier who promotes a school reading challenge while threatening library budgets. Ironic, really, although I wonder if irony is a political concept?

Not so in 1976, Don Dunstan astride an elephant, describing the toys that comforted the crying boy (“…two French copper coins, ranged there with careful art, to comfort his sad heart”). As each, now, is taken away, and placed in a box in the basement.

How can you tell a child to read a book if there are no books?

Why the cuts at the library, anyway? Why not Arts SA, or the Department of Premier and Cabinet? It’s always worrying when culture and politics get too cosy.

I’ve used the State Library for research on each of my books. I’ve spent hours toying (unsuccessfully) with the microfiche machine, sitting, noting, as the guards watch my back, photocopying pages of old newspapers. Simply, I couldn’t do my job without this place.

I know the library would like to do more. So many books by Australian authors languishing in storage because (I assume) of limited space for an unlimited collection (Borges’s was infinite: “There is no combination of characters one can make…that the divine Library has not foreseen”).

To me, the significance is the book we might not read, the idea we might not understand.

In knowledge, people can avoid a lifetime of mistakes, find a better job, an easier path, a catchier song, a tastier recipe, the best cure, the most compassionate words, the most humane way to act, the most logical explanation. All of these things are at stake if libraries become liabilities. Too costly. Not enough economic activity generated, as though that’s the key to everything.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

I visited the State Library as a boy. Learned about Rommel’s tactics, and what sort of plants grew in the Great Sandy Desert. How can you tell a child to read a book if there are no books? Perhaps, as George Orwell suggested, it’s a case of politics adding solidity to pure wind? Or maybe ignorance really is strength?

Libraries need more, not less, money.

In this age of doubt, of dislocation, of confusion, cynicism, the lessons of our past are necessary. They will guide us, if we still have them. Inspire us, if we can stop long enough to listen. The “narrow-minded philistinism” that Borges experienced prior to 1955 is still there. Always will be. Waiting for us to decide that books and reading are no longer worth the effort.

Stephen Orr is an Adelaide-based writer of both fiction and non-fiction. His most recent novel, The Hands, was longlisted for this year’s Miles Franklin Award.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here

Comments

Show comments Hide comments