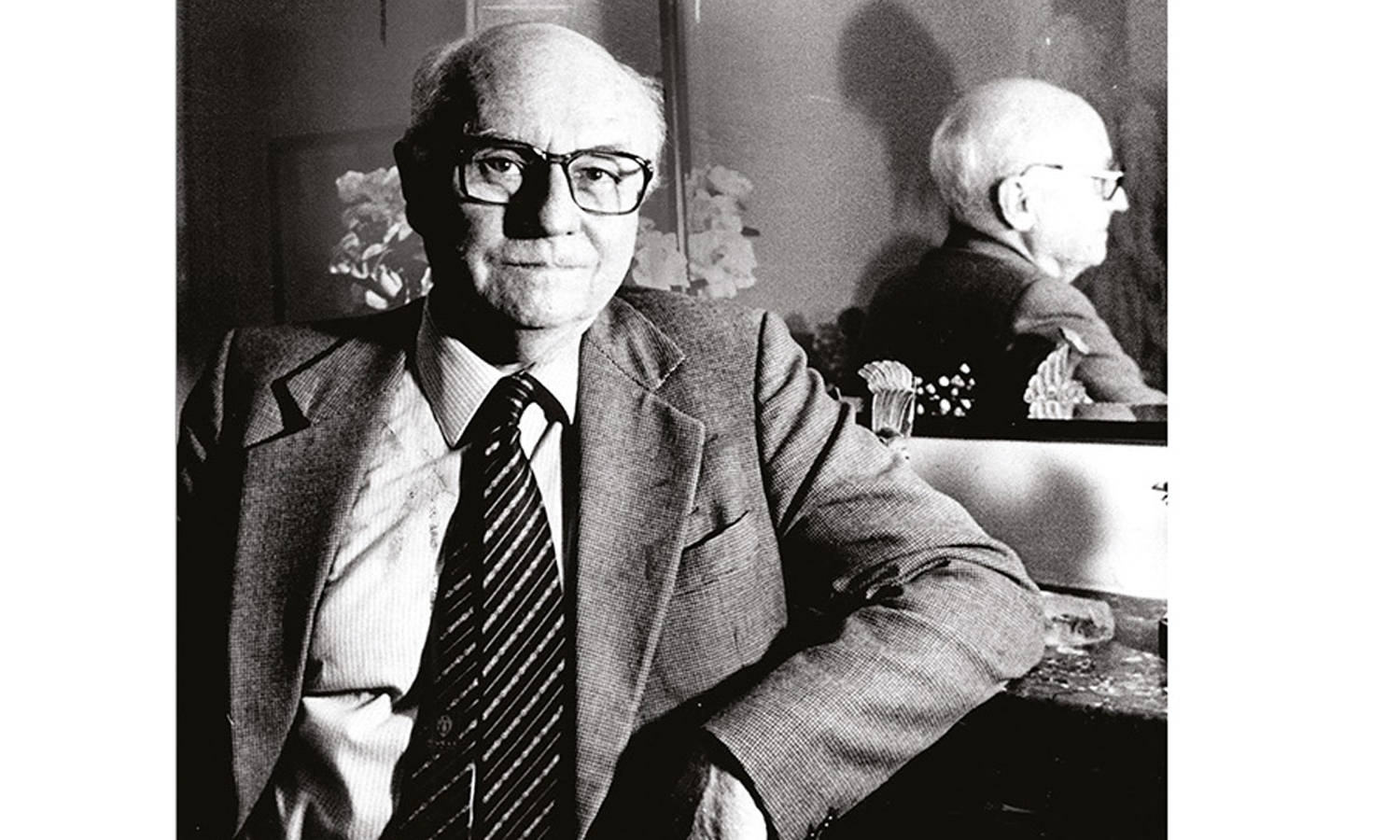

Donald Horne is the man who coined that much misunderstood cliché “the lucky country” and it’s high time we reassessed this fascinating Australian. That cliché was enshrined as the title of his 1964 book, The Lucky Country.

Which is a bit misleading considering that Horne wrote that “Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck”.

Horne is an interesting subject particularly for the way he veered, eventually, from conservatism to a more left-leaning political philosophy.

There are a few famous cases of this phenomenon. Malcolm Fraser comes to mind and, arguably, Robert Manne – mainly on account of his advocacy for refugees’ rights. The mind struggles to come up with another example.

Until now. For this reader it has taken Ryan Cropp’s sweeping new biography to reveal that the renowned Australian writer and social commentator Donald Horne was quite the Tory in his younger days and didn’t change tack until well into adulthood.

Horne was approached to stand for office as a Conservative candidate in 1950, while living in rural England with his young wife Myfanwy. Had he yielded to the temptation, he might have ended his days as a member of – though one can only imagine him an awkward misfit in – the House of Lords.

The unifying strand between his rightist and left-leaning selves, Cropp’s study makes clear, is that, above all other considerations, Horne was nobody’s dupe. He was a man of critical intelligence who accepted very little in life at face value but delved deep until he could discern underlying motives, and then tested his theories by airing them publicly – and awaiting the inevitable reaction.

Born in Kogarah, NSW, on Boxing Day 1921 (13 years before another literary son of that Sydney beach suburb, Clive James), Horne was very much a product of his times. A serious young man from a respectably bourgeois family, he was never tainted by an early dalliance with Marxism but his distaste for the excesses of enforced egalitarianism was stoked by Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, published when he was 15, and Orwell’s Animal Farm, which came out when he was 20.

Cropp identifies two sparks that ignited his subject’s about face from conservatism to true liberalism. One was the fact that too many of his compatriots were being lulled into complacency and conformity during the Menzies years – prompting Horne to warn them against the unconscious torpor induced by a “follow my leader” mentality.

The second spark was ignited by years of working alongside intellectually hidebound characters keen to persuade Frank Packer that in Horne he had appointed an incendiary to edit The Bulletin – a campaign that led to his ousting, despite having lifted the magazine’s sales, and wrenched it from a moribund state into a new era of relevance with his fresh approach to content and presentation.

Horne’s initial revenge was to write a bestseller that made other critical observers (in their tens of thousands) sit up and see, with scepticism verging on dismay, just what kind of society Australia was becoming. As Cropp makes clear, in the era when the monoglot was king, Horne opened Australians’ eyes to the reality “that the much-feted Australian values of egalitarianism and mateship were rarely extended to women, migrants or the Indigenous population”.

Then, his critical edge was stirred to passionate fury when, while hospitalised for an operation to save his sight, he received the shock of the Dismissal; and, as an aftershock in printed form, produced his powerful philippic Death of the Lucky Country.

Few if any writers maintained the rage as fiercely and unremittingly as he. It was burning brightly still two years later when I helped secure him as guest speaker – sharing the stage with Manning Clark, Frank Hardy and Gareth Evans – at a Citizens for Democracy rally in Albury.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

Cropp’s valuable lens on Horne’s life is not only an overdue tribute to a great Australian man of letters (the memoir trilogy that began with The Education of Young Donald is an Australian classic) but stands as an impressive work of scholarship in its own right as he traces a contrarian’s passage across the cultural and political landscape, one deliberate step at a time.

While the odd chronological mistake has evaded his publisher’s editorial eye – according to the author, in early 1961 when Horne took over as Bulletin editor the Soviet Union and China both had nuclear weapons; but that is not so. Beijing didn’t explode its first atomic device until 1964, well after Horne’s tenure at Sussex Street had been terminated, but these blemishes are as nothing compared to the wealth of reasons why, if you care at all for the possibilities of leaving this country better than you found it, you ought to read this account of someone who tossed aside his Panglossian blinkers and trod that path before us.

Donald Horne: A Life in the Lucky Country by Ryan Cropp, La Trobe University Press & Black Inc, $37.99

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here