In her latest novel, Stone Yard Devotional (Allen & Unwin), Charlotte Wood’s narrator reflects that perhaps some things – in this case, a doctor assisting with voluntary euthanasia – can only be done without any expression of feeling. “Perhaps the coldness was the most compassionate aspect of all.”

This particular action, recalled second-hand, is not consequential to the events of the novel. But the event’s texture – cool restraint as a guard against puncturing an unfathomable dam of emotions – mirrors the novel’s crisp narration.

The unnamed narrator leaves her marriage, her job (at a Threatened Species Rescue Centre) and her inner-Sydney flat to live with a remote religious order near her childhood home in regional New South Wales. An atheist, she is drawn less to a community of belief than to quiet seclusion, bare asceticism (“I found the landscape’s desolation beautiful”) and proximity to her childhood home.

In fact, she seems defined more by her loss of faith – in a future for a dying world, in fulfilment from modern urban trappings. “Every minuscule action after waking means slurping up resources, expelling waste, destroying habitat, causing ruptures of some other kind. Whereas staying still, suspended in time like these women, does the opposite. They are doing no harm.”

Charlotte Wood seems to publish novels in two main veins (with, of course, some crossover). The first, epitomised by her internationally successful The Weekend, is cutting, character-driven realist fiction, characterised by brilliant social observation and driven by the tension between what’s expected by society or projected by individuals, and what is messy and real. The second, epitomised by her Stella-prize-winning dystopian novel The Natural Way of Things, is philosophical, and primarily prosecutes or explores ideas. Stone Yard Devotional falls into this second category.

Charlotte Wood seems to publish novels in two main veins (with, of course, some crossover). The first, epitomised by her internationally successful The Weekend, is cutting, character-driven realist fiction, characterised by brilliant social observation and driven by the tension between what’s expected by society or projected by individuals, and what is messy and real. The second, epitomised by her Stella-prize-winning dystopian novel The Natural Way of Things, is philosophical, and primarily prosecutes or explores ideas. Stone Yard Devotional falls into this second category.

The novel is driven by the narrator’s relentless reflection and moral questioning, set against memories of her earthy, practical, “kind” mother, who routinely performed acts of public good (like looking after refugee children, or visiting the dying) and resisted the false or performative (like a neighbour’s experiment in mystical Catholicism).

What is it to be good? How is goodness shaped, assisted or constrained by the society we live in and our place within it? What is the nature of forgiveness – and how do we earn it? What are the relative benefits of belonging to a community and existing outside it?

They’re fascinating questions, and the novel is peppered with memories and reflections that explore and complicate them. (It’s also richly woven with moments that speak to an idea that runs throughout all Wood’s novels: “Nobody knows the subterranean lives of families.”) These questions – and our understanding of the narrator – are further complicated by the arrival of a figure from her past, bearing the bones of a murdered nun back to the religious order for burial.

Wood is an exquisite writer. This is reflected in her beautifully crafted sentences, her always impressive ability to draw a vivid, palpable sense of place – and in her perfectly pitched descriptions of a mouse plague that descends on the community. Though COVID is also present in the novel – glancingly, as the community lives such an isolated existence – it feels like the mouse plague represents the way the biological one intimately infiltrated our lives. The narrator notes “the muffled flapping of the cockatoos’ wings as they swoop down to the bath resembles the sound of the mice scuttling in the night. The mouse plague is infecting everything now: all sense of smell, of course, but even sound, even memory.”

South Australian writer Lucy Treloar’s third novel, Days of Innocence and Wonder (Picador), is in many ways very different from Stone Yard Devotional, but it’s also another COVID-era novel centring on a narrator who flees her city life for country isolation. And her narrator, Till, is similarly taciturn. Her constraint, too, is a guard: Till is forever marked by her best friend’s abduction from the kindergarten gates when they were four years old.

South Australian writer Lucy Treloar’s third novel, Days of Innocence and Wonder (Picador), is in many ways very different from Stone Yard Devotional, but it’s also another COVID-era novel centring on a narrator who flees her city life for country isolation. And her narrator, Till, is similarly taciturn. Her constraint, too, is a guard: Till is forever marked by her best friend’s abduction from the kindergarten gates when they were four years old.

In fact, Till is not even her name – she changed it in the years after the event. Similarly, she never speaks the name of her lost friend, referring to her simply as “S”. Her all-black wardrobe, outwardly a mark of Brunswick bohemia, is also revealed to stem from the event; she is afraid of being noticed. “Nothing had happened to Till, but something happened all the same.” Since, she has lived her life parallel to the lives around her, and to her memories. She is a watcher.

The novel begins with Till’s sudden journey from Brunswick, driving to… she doesn’t know where. “She is being stalked, so she ran.” It takes a very long while until we get a sense of what she is running from, and how real the threat is. As she drives, she stumbles on Wirowrie (a town based on Terowie), an almost-ghost-town, with a tiny population and a main street consisting mainly of abandoned buildings, and sets up overnight camp in the old railway station, a crumbling sandstone structure.

The overnight stay extends and she slowly becomes a resident of this tiny place, gaining the protection and friendship of the locals, who give her work, befriend her greyhound, Bird, and help her restore the station walls. One local who remains a threat is the policeman. And she slowly learns that this place has seen tragedy, too, including the disappearance of a local woman and the death of her partner, an Indigenous man.

A sense of foreboding – and the lingering grip of the past – co-exists with a growing sense of community and belonging. Like Wood, Treloar deftly inhabits the novel’s setting. It was easy to imagine myself inside the sandstone station with its restored leather waiting-room couches and small fire, or with Till, walking Birdy along the station platform in the dark.

“The sad, growling anger that was part of her had moved off a little way, at least most of the time. She would not easily leave a place that had done that.” And so she settles in. But the past hasn’t finished with her yet. And the driving menace that the novel opened with returns to unsettle not just Till, but us as readers – building to a nail-biting conclusion.

Days of Innocence and Wonder is a sensitive, admirably complex exploration of trauma and how it manifests, and of toxic male violence. It’s also a gorgeous inhabitation of remote rural South Australia.

Most people I know would probably be surprised that I was one of the eager first readers of Henry Winkler’s memoir, Being Henry: The Fonz … and Beyond (Macmillan). If their main association with Winkler is Happy Days’ rebel with a heart of gold, Arthur Fonzarelli (aka The Fonz), or the dodgy family lawyer in Arrested Development, or Winkler’s memorable cameo as a murdered high-school teacher in the first Scream movie, they’d also be surprised that while I loved The Fonz as a kid, I was drawn to this memoir for the way Winkler speaks and writes about trauma. (If you’re a fan of Winkler’s greatest role, as egotistical acting teacher Gene Cousineau in HBO’s Barry, you might be less surprised by the trauma association.)

Most people I know would probably be surprised that I was one of the eager first readers of Henry Winkler’s memoir, Being Henry: The Fonz … and Beyond (Macmillan). If their main association with Winkler is Happy Days’ rebel with a heart of gold, Arthur Fonzarelli (aka The Fonz), or the dodgy family lawyer in Arrested Development, or Winkler’s memorable cameo as a murdered high-school teacher in the first Scream movie, they’d also be surprised that while I loved The Fonz as a kid, I was drawn to this memoir for the way Winkler speaks and writes about trauma. (If you’re a fan of Winkler’s greatest role, as egotistical acting teacher Gene Cousineau in HBO’s Barry, you might be less surprised by the trauma association.)

“When I was on a stage, playing someone else, I was transported to another world, one where pretending made you successful,” he writes in his opening pages. “What I was miserable at was being myself… it’s taken me fifty years to realize that there really is a me inside me.”

Winkler was the son of German Jewish parents who left Berlin in 1939, managing to escape by pretending they were on a business trip. Winkler’s father covered the family jewellery in melted-down chocolate to smuggle it out, and lied to his wife to get her to accompany him. After they left, “the Nazis murdered … my father’s and mother’s whole families”.

Winkler, who only discovered his “severe” dyslexia aged 34 (and writes about how hard it was to read his scripts), never felt loved by his parents, who were “embarrassed” by his abysmal grades and called him “dummer Hund… dumb dog”. He barely passed high school, but managed to get into Yale Drama School. Soon after graduating, following a short stint acting in commercials, he moved to Los Angeles and soon got his Happy Days audition, and the role that made him a star.

What is astonishing – and very endearing – about this book, and Winkler’s story, is his candid honesty and open vulnerability. He was a high-school outsider who longed to hang out with the cool kids and tried too hard, then had a similar trajectory with women (until he became The Fonz). Winkler writes about taking an old classmate up on her casual offer to crash on the couch any time – and not noticing her horror when he arrived with his bags at her studio apartment. “Was I reading the social cues? Not even close,” he writes about a similar experience. And that phrase applies to so many anecdotes.

There’s the time he kept calling Paul McCartney to hang out after they met on the street once, and when he called producer James L Brooks to ask if he’d offended him with a comment at a party, after days of sleepless night obsessing about it. When he first met his future stepson, Jed, the eight-year-old opened the door and said: “Fonzie!” Winkler said: “My name is not Fonzie. My name is Henry. Would you like it if I called you Ralph?” He’s felt bad about it ever since.

This isn’t in the book, but I can tell you that while Henry Winkler might have done a bit of unwelcome couch-surfing as a young actor, he made up for it later. Actor Marlee Matlin asked to stay in his pool house for a couple of nights after she left her abusive boyfriend William Hurt, the night she won an Oscar. She stayed for two and a half years, got married in his backyard and calls him a second father. This story is what made me interested in Henry Winkler, beyond him being The Fonz. An interview on NPR’s Fresh Air about his childhood is what made me buy the book. And having read it, I’m a bigger fan than ever.

Another person I feel like I grew up with is Kaz Cooke, whose humorous, well-researched, common-sense-based health and lifestyle books seem to have been there since I was a teenager. I read her columns in Dolly magazine, and her no-bullshit beauty book Real Gorgeous was a comfort. Her pregnancy book Up the Duff was published just a little too late for me – around the time my my son was born – but I’ve bought many gift copies for friends. And I was kind of pissed off that they got sensible cool-girl Kaz, while I had to make do with the preachy, treacly What to Expect When You’re Expecting.

Another person I feel like I grew up with is Kaz Cooke, whose humorous, well-researched, common-sense-based health and lifestyle books seem to have been there since I was a teenager. I read her columns in Dolly magazine, and her no-bullshit beauty book Real Gorgeous was a comfort. Her pregnancy book Up the Duff was published just a little too late for me – around the time my my son was born – but I’ve bought many gift copies for friends. And I was kind of pissed off that they got sensible cool-girl Kaz, while I had to make do with the preachy, treacly What to Expect When You’re Expecting.

But while I missed out on Up the Duff, I’m generationally well timed for Kaz to be on hand as my wise, well-informed friend as I hit my late 40s, with It’s the Menopause (Viking). In my experience, a book has to feel just right for a sensitive subject like this, which is as much about your changing sense of self as a biological process. I tried a book to make me feel less alone in perimenopause a year ago, but its cringey humour only made me feel old and silly. I actually hid the book from myself so I wouldn’t have to see it – then couldn’t find it and had to pay a library fine. (My husband found it outside under a cushion a few months later.)

Cooke brings together advice from menopause doctors and other experts with the voices of around 9000 real women, sharing their own experiences. That survey, she writes, is not scientific, as it was an opt-in online survey – but it is the biggest collection of data in Australia so far showing women’s thoughts, feelings and experience of perimenopause and menopause. Those quotes are “the backbone” of the book, which aims to feel like a big conversation, with medical facts.

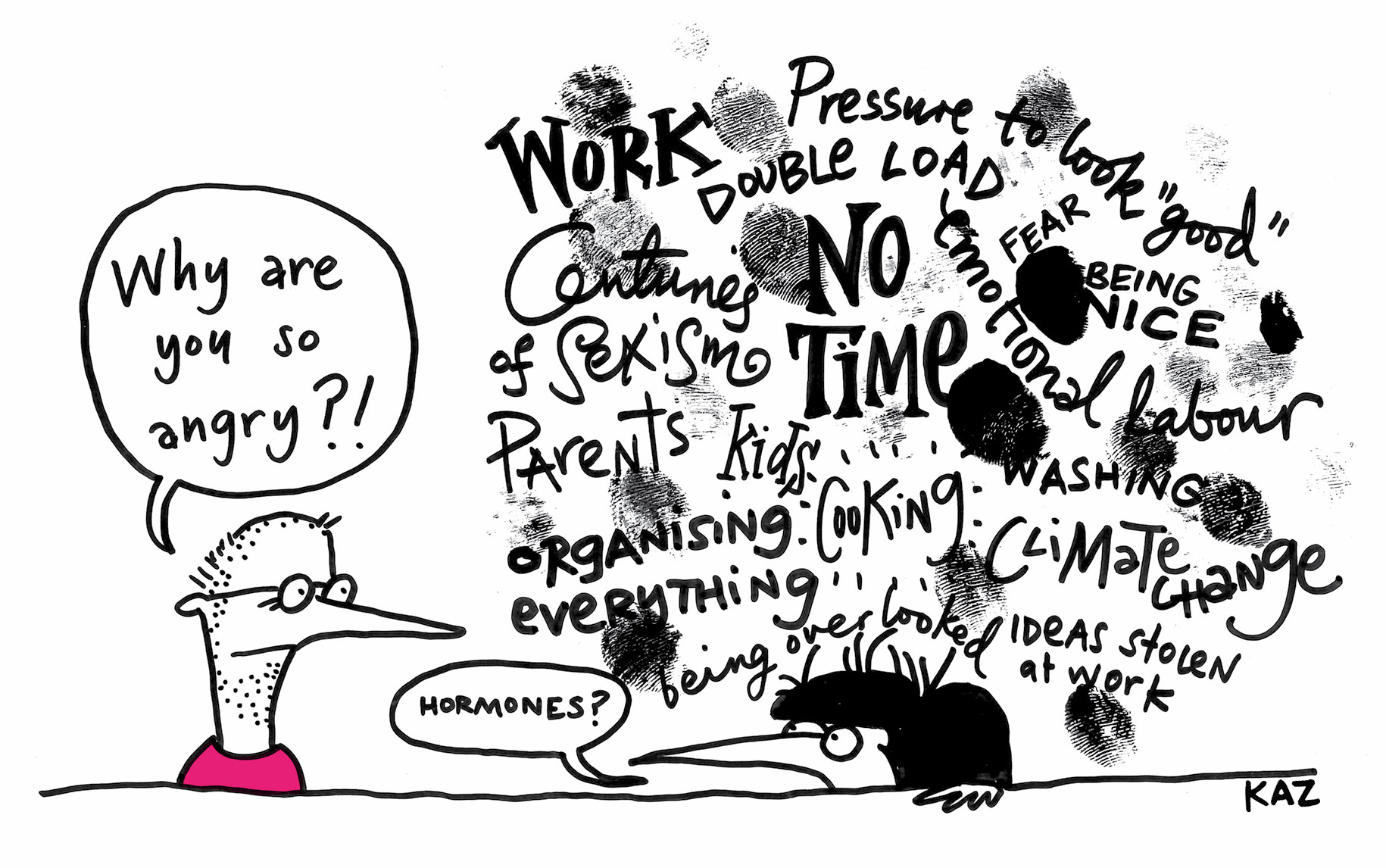

Cooke writes that most people won’t read the book from cover to cover, so much as browse for what they’re looking for. And while I’ve done an initial read, I can tell that’s how I’ll use it, too: as a reference/companion. The book is impressively navigable, with bold, colourful subheadings throughout, lots of checklists (like: possible symptoms of perimenopause and menopause, what estrogen does, things that can help combat stress), pop-out quotes from real women sharing their experiences, and comic-relief cartoons.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

I really like that this book considers practicalities like how much things cost and what we can afford, that it untangles what marketers will tell us we need to buy from what we might actually need, and that it offers ways to feel less crap about the aesthetic effects of menopause. As one contribution to the latter, Cooke tells us to “feel free to cut the size labels out of your clothes”. And another: “If miracle anti-ageing products and procedures really worked, most influencers would have aged their way back to toddlerhood.” Haha. That’s my funnybone tickled.

No need to hide It’s the Menopause – it will have a place of pride on my bookshelf for a very long time.

Angry, by Kaz Cooke, from It’s the Menopause.

Jo Case is a monthly columnist for InReview and deputy editor, books & ideas, at The Conversation. She is an occasional bookseller at Imprints on Hindley Street and former associate publisher of Wakefield Press.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here