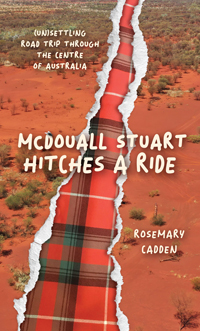

A solo road trip through the centre of Australia from Adelaide to Darwin is the backbone of my book McDouall Stuart hitches a ride.

It’s a rollicking ride, starting with pesky flies and the bumpy gravel roads of outback lite into ‘oh, shit, what have I let myself in for’ as I lay in my swag in the middle of the desert, fretting about the source of that bump in the night.

The bumpiest ride of all, however, was yet to come – a research journey that lasted eight years. It had me delving into the stories told of this country I now call home; the fake news and missing moments – hidden, sidestepped, ignored.

McDouall Stuart and I come from the same hometown on the east coast of Scotland. We both emigrated at 22, looking for adventure. He was on one of the first migrant boats to the fledgling province of South Australia in the 1830s, while I was on one of the last (legally sanctioned) ships bringing immigrants to these shores in the 1970s. He was an obvious travelling companion.

McDouall Stuart and I come from the same hometown on the east coast of Scotland. We both emigrated at 22, looking for adventure. He was on one of the first migrant boats to the fledgling province of South Australia in the 1830s, while I was on one of the last (legally sanctioned) ships bringing immigrants to these shores in the 1970s. He was an obvious travelling companion.

It was the statue of McDouall Stuart in Alice Springs that had me questioning my choice. There had been a protest calling for the statue to be removed and accusations about him being involved in violent encounters with First Nations people. Up to this point, I’d heard only good things about his dealings with the original inhabitants. It had me questioning myself, challenging my beliefs, my biases and preconceived ideas.

In a time when many of us want to better understand our history, the explorer’s constant presence on the trip and the people I met along the way forced me to question what I know and how much I still have to learn.

The following excerpt is from chapter 24 of McDouall Stuart hitches a ride, when I leave Alice Springs and continue my journey north.

———–

Who do you think you are?

Road trains, kangaroos and grey nomads. The three dangers for drivers on the Stuart Highway. The motto for all three: Keep Your Distance.

You’d think the Stuart Highway would be a multiple-lane affair, befitting Australia’s first transcontinental highway and the principal north-south route through the centre of the continent. Turns out it’s single file each way, with few offers of a hard shoulder for emergencies. Slide over the fraying edge of the bitumen and you could end up with more than a gravel rash.

‘The Track’ or ‘The Bitumen’ are the names given by folk who use it regularly. Exploring not being their top priority, they know little and care even less about the man who gave the highway its name. They’re too busy transporting freight across the continent or just want to get where they’re going. As fast as possible. I keep stopping and pulling to the side to let them pass. Bad-Ass Betsie seemed so big, drawing attention to herself, on the streets of Adelaide. She was just the right look for the Oodnadatta Track and the Old Ghan Railway Trail, your reliable and capable outback lass who could go where others – too puny or too precious – feared to tread. This is different. I’m intimidated.

Another road train screams up behind me, a hundred tonnes-plus of heavy metal filling the rear vision mirror, headlights blazing, horn blaring. A trembling window separates me from the towering wheels hurtling past. One trailer, two, then a third, a never-ending blur of circling fury sucking me sideways into a vacuum. I cling to the steering wheel. Keep in a straight line, I beg my Betsie. Another prime mover looms from the opposite direction, towing a couple of trailers, the turbulence leaving me and Betsie shaking and shuddering. These monsters, the length of an Olympic swimming pool, stop for no one. They have so many wheels, if one blows out, they keep on keeping on. That explains the ribbons of rubber strewn along the highway.

I spy what looks like a black bedsheet flapping in the distance. As I approach, the sheet rises into the air, splitting apart, turning into a couple of wedge-tailed eagles that have been scavenging the bloody carcass of a kangaroo lying across the road.

Kangaroos are in their millions in the Northern Territory, far outnumbering humans, who amount to around 250,000. While Skippy looks cute bounding across a paddock, he is not so attractive if his ninety-kilogram body bounces onto your car bonnet. As a lump of roadkill, he’s an accident waiting to happen to you. Bad-Ass Betsie and I were lucky to keep our distance – this time – from Danger Number Two, but I’m guessing it won’t be the last encounter.

It’s single file each way on the Stuart Highway. Photo: Rosemary Cadden

Not far out of Alice Springs, Bad-Ass Betsie and I veer off the Stuart Highway where the map shows a cross-hatching of minor roads. A signpost to Gemtree Caravan Park beckons. Its website offers an escape from the hustle and bustle and that’s exactly what I get. There’s a rustle and a kangaroo, hidden until I disturb him, hops away from me towards the sun dipping down, the tips of his fur glowing reddish-brown. The golden hour. Who needs fluffy towels in a five-star hotel room?

Celia, a government relief worker and my only companion in the campground, is horrified when I admit all I want to do on Stuart Highway is pull over and cower when a road train appears. ‘God, no. Keep your nerve and keep up the speed,’ she says.

‘Think about it,’ and she begins to talk very precisely as if I might be a bit slow on the uptake.

‘If you slow down, the truckie coming from behind has to slow down too.’

She also tells me to make sure I have a clear path of more than 1.5 kilometres on the other side of the road should I want to overtake one of those metal monsters. That advice was unnecessary.

I face the truth and raise my cup of tea. ‘My name’s Rosemary, and I’m a grey nomad.’ Danger Number Three. That’s me with my Bad-Ass Betsie, a name that she totally owns: part profane, part twee; the perfect name for a grey nomad’s vehicle. Tens of thousands of grey nomads – of us – are out there at any one time, taking our time. Too much time for some. The legal limit for cars on some sections of the Stuart Highway is 130 kilometres an hour, the highest in the country. Not so long ago, the Northern Territory government played around with no limit at all. If I get to 100 kilometres an hour I think I’m doing well. ‘Travelling baby boomers’ is another title we get; in the United States it’s the rather romantic-sounding ‘snowbird’; here in Australia it’s ‘old farts’.

I have a bigger truth to face than being a slow coach. As a migrant I’ve sometimes felt like an outsider and, while probing Australia’s colonial history, a bit of an onlooker. But the goalposts have moved. That statue back in Alice Springs has got me probing my relationship with this country I now call home. In the citizenship ceremony, you accept your rights and your responsibilities as an Australian citizen. I’m embracing the right to question, to criticise as well as praise what is done in our name and, if asked, ‘Who do you think you are’, I can answer with a firmer footing. To acknowledge our colonial history, I now recognise, is a responsibility for everyone. McDouall Stuart was part of the settler colonisation process in South Australia, as I am now.

Bad-Ass Betsie in the outback. Photo: Rosemary Cadden

In McDouall Stuart’s day, colonising nations around the world saw themselves as bringing civilisation to barbaric and savage nations. When I came to Australia, that paternalistic attitude and the sense of superiority and entitlement wasn’t far below the surface. If you did mention colonisation, it was okay if you associated it with modernity, progress, and development. Anything else was un-Australian.

Settler colonisation, what we have in Australia, goes further than an attitude of entitlement to plunder the land and its resources and use the inhabitants as cheap labour. The powers that be were intent on establishing themselves as the new and rightful inhabitants of Australia. That First Nations people would soon die out was not just a belief, it was the plan.

Shunting the original inhabitants onto missions and denying them access to their country exposes the reality of a system geared to take over completely. Same with the policies that tried to erase language and culture, that legitimised taking children away from their parents, that controlled their every move, who they could associate with, where they could go.

And the effects linger on.

Did McDouall Stuart ever question himself, what he was doing? His motives for doing all this exploration?

‘I’ve heard of him,’ says Celia, when I tell her I’ve been following McDouall Stuart’s route through the centre of the continent. ‘I like the way he went about things,’ she says.’ ‘Burke and Wills overstretched themselves, while Stuart, he knew when to stop and when to keep going.’

Do I know when to stop, when to keep going?

———–

Rosemary Cadden has worked as a journalist, media adviser and PR consultant with a special interest in environmental issues and history. It was when she worked for Aboriginal organisations in South Australia and the Northern Territory in the 1990s that she was drawn to explore the effects of settler colonisation. For more information about McDouall Stuart hitches a ride ($35), check the author’s blog.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here