Poetry is not confined to words.

Alex Frayne plucks peerless lyricism through the eye of the camera.

It is not that he is a good photographer, it is that he is an artist with photo lenses. It is in his perception of the world and in the way that he delivers it.

Frayne has become the Ansel Adams of our time but, unlike Adams, he has a realm of new technology at his call as well as the classic single-lens-reflex cameras he long has favoured.

In this new book, Distance and Desire, there are images of breathtaking perfection, some achieved with a simple smartphone camera. It is all from the eye of the beholder. He sees and seizes.

Time is the great abstraction and we cannot make it stop let alone turn it back. Unless we are Frayne with a camera, waiting, like a cat patiently poised for a movement from live prey, and then pouncing, with a click. And there it is. Perfect light in a perfect moment. A Frayne vision.

Time is the great abstraction and we cannot make it stop let alone turn it back. Unless we are Frayne with a camera, waiting, like a cat patiently poised for a movement from live prey, and then pouncing, with a click. And there it is. Perfect light in a perfect moment. A Frayne vision.

Oddly, Frayne’s reign as master of light really began without the light.

His rise emerged from Adelaide by night, with a striking Adelaide Noir series for which he prowled through the dark hours of the city and exposed an underbelly few of us had ever seen. He liked doing it in winter when nights are still and moonlight and street lights are bright. He used only this ambient light and long exposures. He became an expert on street lighting, noting the dramatically varying hues from tungsten, fluorescent, and sodium lighting.

This work initially was exhibited on Facebook and RedBubbble, but it soon gained a cult following which materialised into the first of his four books.

Ironically, when dealing with the frailty of momentary image, he is now, through Wakefield Press, producing very big books. Heavy. Strictly table-top viewing. And they are not page-turners. They are page-lingerers. And emotion-evokers.

His new book is a tome of visual poetry.

Frayne delivers feelings of time and place, feelings of and for nature and time and the fragile nature of life. His images are more than photographs. They are experiential. They also include whimsy, humour, and delicious incongruity.

As Frayne has said, he may be driving along with directional purpose, but a flash in the corner of the eye can stop him in his tracks with an unexpected visual treasure.

In Distance and Desire, one is captivated time and time again by the timeless immediacy of “now” and that elusive being we call light. It changes constantly.

Mad dogs and Englishmen may go out in the midday sun – but not Alex Frayne.

“I never shoot during the middle of the day,” says he. “I always shoot either early in the morning or late afternoon; it’s an essential discipline to train yourself to shoot at these times.”

But why?

“It’s because when the sun is sitting in a lower position in the sky it yields longer, more accentuated shadows. This gives the frame length and depth. Return trips are often required to find the right light and mood.”

Thus patience and persistence are among the character traits inherent in his fine art photography.

Stomp, by Alex Frayne: ‘It is rare to see fog in the city. But when it does occur it lends an extra layer of mystery and marvel to an already beautiful landscape in the parklands.’

Frayne sidled into plein-air photography from a former life as a filmmaker. He had gained a BA in cinema and photography at Flinders and was rolling along successfully in film with a successful feature film callled Modern Love under his belt, as well as assorted shorts and documentaries.

Hunting out locations for Film Corporation shoots gave him a new perspective on the power of place. And the phenomenon of Adelaide art photographer Alex Frayne was born.

Among his professional idiosyncrasies is a love for the very basic in photographic gear. No truckloads of lenses. He prefers analogue film formats (120 and 35mm film) to digital, and scans his rolls of film – developed in a home darkroom – to the digital format.

This, he says, allows him to keep “control of the images from go to whoa without compromising the work at any stage”.

Then again, he is not beyond using his iPhone if there’s a spontaneous opportunity.

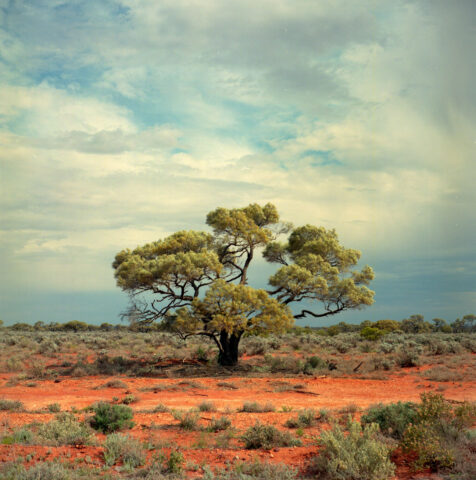

Solo Tree, by Alex Frayne: ‘An image made near Kingoonya featuring a myall tree growing defiantly in an arid landscape.’

Weather is both a subject and a consideration in his world. Wind is an enemy, albeit he makes it a subject of windy sandy dune images.

“Cameras are allergic to sand and wind, as I have discovered on numerous occasions,” he laments.

“And wind is perilous when skirting around cliffs and coasts [see the photo ‘Windy, windier, windiest’ on page 66 of Distance and Desire]… you need sure footing and adequate camera gear protection to avoid disaster.”

Lightning is enemy number one but, once again, a literally brilliant subject featured in the book. “Supercharged”, on page 37, tells this story. However, adds the artist, “a few photographers have met their demise with the tripod acting as a lightning rod”.

“For anyone interested, if you feel your hair rising on your scalp in your lightning event, you need to RUN AWAY and seek cover!”

Knight’s Beach, by Alex Frayne: ‘A monster wave at the Port Elliot surfing spot on the South Coast. It’s times like these that I’m glad to be using a 400mm zoom lens, and nowhere near the action.’

A lot of country travel was involved in the making of this latest book. But main roads or back roads all harbour potential for big landscapes and close observations, yielding comment on perchance the politics of time and place. Such reflections are imparted with immense poignancy in some of his shots of the failed dreams of farmers and the crumbling ruins of rural hopes out there on the landscape.

Frayne is fascinated by ghost towns.

“With the state’s mining and wheatbelt history looming large as I traverse the state, I see the hopes and dreams and nightmares of the post-colonial world colliding with modernity,” he says.

“This frisson is fascinating and seems almost made for photography.”

He cites the book’s photos of Tarcoola, “the only real ghost town”, and “20th Century Restaurant” at Iron Knob as favoured examples of the lost-world triste.

Frame has pictured “Summer Hedonism” on the Port Willunga sands with the amazing bleached hue of a Charles Conder painting. His study called “After Rain”, of the red dirt scrub near Roxby Downs, sings a song of David Dridan.

He captures Heysen light in the world of eucalypts, and in one mind-blowing study of ancient trunks he out-Heysens Heysen for ever.

A Stepney back street view is like an ode to Jeff Smart. There are shades of Streeton, Baines, and Trenerry throughout the pages. Not that this can be deliberate. Rather, it is a greatness and fluidity of landscape art. And, perchance, a beautiful truth of place.

8 bit fish and chips, by Alex Frayne: ‘A monochrome image of the archetypal Australian shop. The challenge with shots like this is to get a long enough gap in traffic on a main road to allow a 5 second long exposure.’

Celestial studies, shades of the sea’s blue from azure to sapphire and cerulean to turquoise, fields of gold and taupe and amber, straight country roads going into infinity, briskly expressive monochromatic studies of contours and old towns, silhouettes and lonely rustic outbuildings, unoccupied benches in a big sky world… every image offers philosophic reflection and poetic implication.

From the Coorong to Bute, from Kangaroo Island to the Nullarbor, and Beltana, Yunta, Kersbrook, Myponga, Ceduna, Coffin Bay, Orroroo, the Limestone Coast, the Mallee, Yorke Peninsula, the Riverland and, of course, all about Adelaide and environs. Frayne’s been everywhere.

Publisher Wakefield Press has called Distance and Desire his “deep dive” into the South Australian landscape and he certainly shows the world how vast and diverse it is.

Photographer and former NIDA head of acting Tony Knight has written the foreword to the book, pointing out the “deep listening” evident in Frayne’s imagery, the way he conveys the essence of place and the sense of back-story. Frayne’s own commentary parries with Knight’s in what, in itself, is a magnificence of introductory composition; it is a joy to read.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

Knight suggests that the audiences may, if they listen as well as gaze upon the photographs, “just hear the ghosts, memories and remembrances of things past”.

Distance and Desire, by Alex Frayne, is published by Wakefield Press and available now. It follows Frayne’s previous books, Adelaide Noir, Theatre of Life and Landscapes of South Australia.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here