Commentary

ReadHas a ‘neoliberal’ festival fixation undercut our cultural community?

In this extract from her book Beyond the Books: Culture, value, and why libraries matter, writer and researcher Heather Robinson reflects on how the rise of an economically driven ‘Festival State’ risks leaving vital institutions out of the conversation.

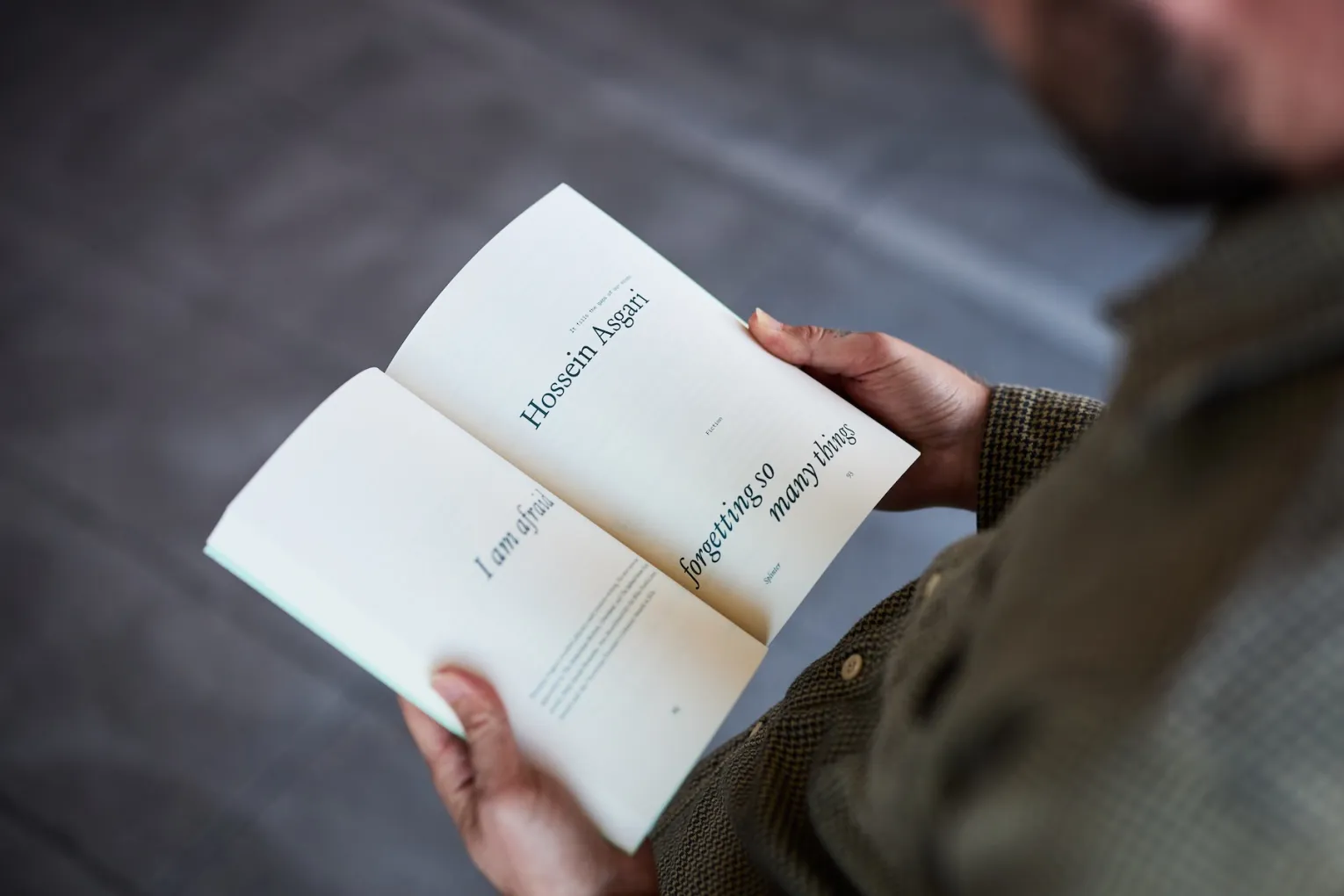

Books & Poetry

ReadThe soft and quiet power of Australian literature needs public champions

Following the abrupt closure of Australian literary journal Meanjin after 85 years, Splinter journal editor Farrin Foster reflects on how literature’s quiet power makes it one of our least-valued art forms.

Music

ReadAdelaide Guitar Festival review: Lau Noah and Lior

A double bill of guitar-driven singer songwriters saw Lau Noah prove far more than an online success story, while Lior offered a thoughtful cross-section of his past and present.