The 2004 Adelaide Ring was an extraordinary, albeit one-off, creation – a comet that blazed and then disappeared, leaving us with outstanding photographs and audio recordings. South Australians should be immensely proud of what was achieved and, 20 years later, this is a good time to remember it and celebrate.

The performances were highly successful in terms of audience reaction, national and international reviews, and peer judgments. The production and artists won an unprecedented 10 Helpmann Awards. A Super Audio CD recording was made of the complete cycle by Melba Recordings, which took the performances to the world and, in the process, garnered praise and awards including the Prix Lauritz Melchior, awarded by France’s Académie du Disque Lyrique to the singers Stuart Skelton and Timothy Mussard.

Around 80 per cent of the audience came from interstate and overseas, and the economic impact on the South Australian economy was valued at $14.2 million – much more than the related expenditure by governments.

The production concept and designs won consistently glowing reviews. The Advertiser critic was extravagant in his praise: “This is, without reservation, the most astounding night of theatre the Festival Centre has ever witnessed. It is probably without parallel in Australian opera history for its courage and audacity. Each act was greeted with tumultuous applause and the final scene with a ten-minute standing ovation.”

Interstate media were just as enthusiastic, with the Sydney Morning Herald critic describing the whole Ring as “one of the finest occasions in the history of Australian music, opera and theatre”.

Overseas, London’s Sunday Times lauded “one of the most visually resplendent Rings of recent times”. Opera Now magazine said: “The results were so dazzling that the sets often won loud applause on their own”. Hugh Canning, in UK-based Opera magazine, wrote: “Elke Neidhardt, with her team … [has] come up with one of the most beautiful, thoughtful and spectacular stagings of recent times.” He also ventured that “it is unthinkable that it should not be seen again in Australia”.

Unfortunately, the unthinkable did happen, and the production was not seen again in Australia or anywhere else. We can be immensely grateful, however, for the Melba recordings and for the superb photographs.

Die Walküre Act III: Elizabeth Stannard as Gerhilde, Gaye MacFarlane as Siegrune, and Donna-Maree Dunlop as Rossweisse. Photo: Sue Adler

The 2004 Adelaide Ring was the first completely Australian-designed and produced cycle of Wagner’s astounding work. Conducted by Asher Fisch and directed by Elke Neidhardt, it took to the stage of the Adelaide Festival Centre’s Festival Theatre three years after another Australian Wagnerian first – Parsifal, directed by Neidhardt and conducted by Jeffrey Tate.

It was Tate who, three years before that, had first come to Adelaide with a Ring from the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. Pierre Strosser was that production’s director, and he supervised the 1998 Adelaide staging, along with two assistants. Not since the British Quinlan Company had brought its travelling Ring to Melbourne and Sydney in 1913 had Wagner’s great cycle of four music dramas been staged in its entirety in Australia, although there were some uncompleted attempts by the Australian Opera in the 1980s.

When the idea of producing the Ring in Adelaide was mooted in late 1994 and given State Government endorsement the following year, it was widely seen as an important cultural tourism initiative. Many prominent South Australians supported the project, as they had supported the foundation of the Adelaide Festival of Arts four decades earlier. The ground-breaking 1998 Ring introduced thousands of Australians, including many politicians and bureaucrats, to Wagner in general and to the Ring in particular, and proved beyond doubt that South Australia was ready to stage an original version of this most demanding of operatic works.

Götterdämmerung Act III: Lisa Gasteen as Brünnhilde, Timothy Mussard as Siegfried, Duccio dal Monte as Hagen. Photo: Sue Adler

The Ring is a drama of ideas. It belongs to no particular period but makes timeless statements about the destructive consequences of man’s ruthless lust for power and greedy exploitation of nature. Wagner described his music drama in four parts as “A Stage Festival Play for Three Days and a Preliminary Evening”. Altogether, it comprises 15-16 hours of music, and its principal themes are the politics of power, the existence and nature of evil, and the redemptive quality of unselfish love – all framed in a world of nature never before or since so vividly portrayed.

Needless to say, the practical requirements of putting together a major work like the Ring are formidable.

For the 2004 Ring, rehearsals were spread over seven months (14 weeks in 2003 and 15 weeks in 2004). Altogether, the Festival Theatre was occupied for more than five months, for which the hiring costs alone totalled $2.6 million.

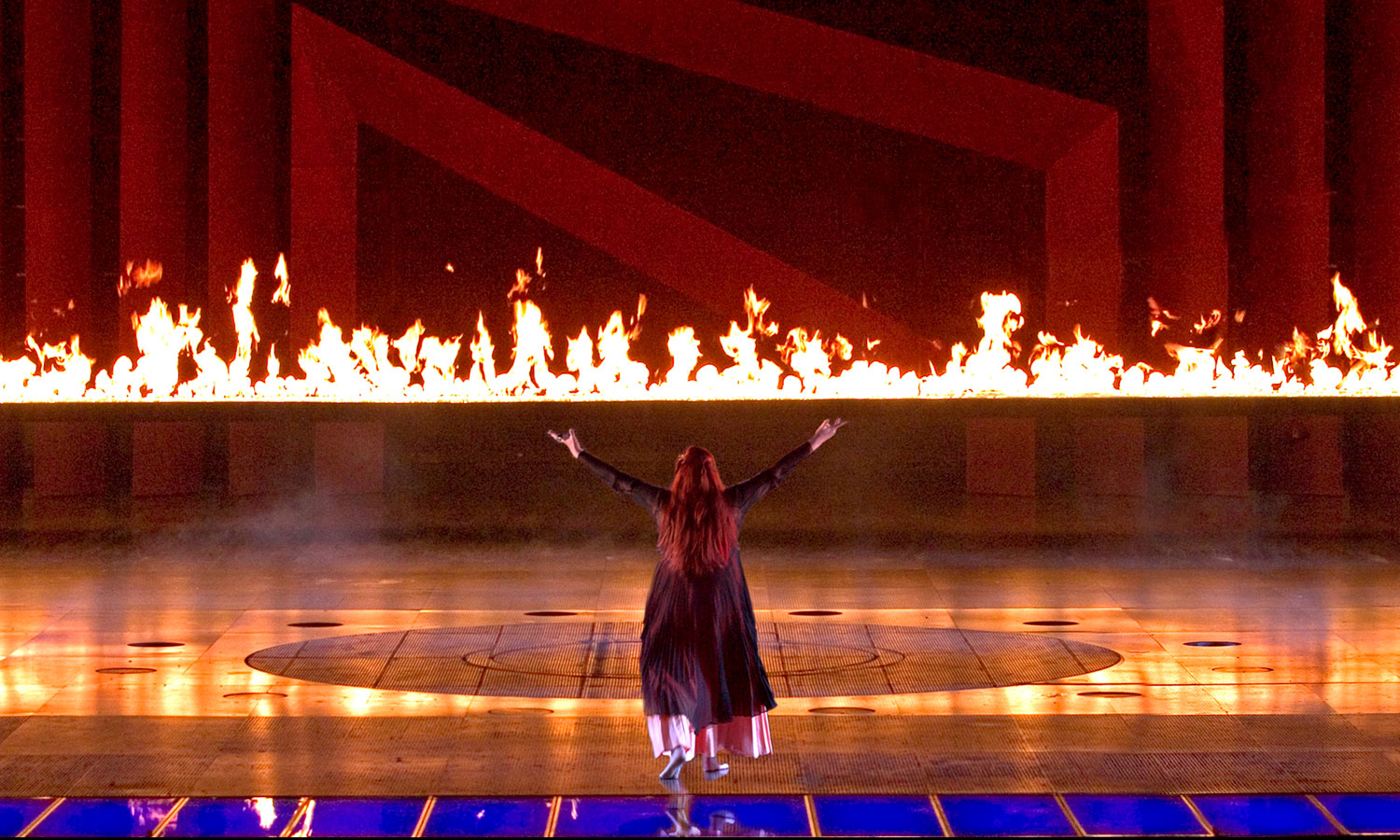

The Festival Theatre has one of the largest stages in Australia and the largest proscenium arch, and this made possible some tremendous scenes. Water and fire are persistent elements in the story of the Ring, and it seemed natural that they should feature prominently in this production. One image that had fired Neidhardt’s imagination was the enormous cauldron which Michael Scott-Mitchell had designed for the Sydney Olympics opening ceremony in September 2000; it rose out of the water and blazed high above the stadium. As a direct consequence, a circular platform which rose and fell on a central pillar surrounded by jets of flame became a key feature of three parts of the Ring cycle: Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung.

The notion of a “water curtain” filling the entire proscenium space was another powerful image, as was Scott-Mitchell’s concept of the “Rhine frame” – a frame of blue Perspex panels lit from behind, which surrounded the proscenium arch and was a constant reminder of the proximity of the River Rhine in, on, and beside which most of the drama takes place.

Das Rheingold Scene I: The Rhinegold seen through the waters. Photo: Michael Scott-Mitchell

The orchestra pit, which is already quite large, was made even larger by breaking through the rear wall and extending the orchestra back under the stage into what is normally an instrument storage room. A total of 130 musicians were engaged for the 2004 Ring, augmenting the 80 permanent players of the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra by another 50. Members of interstate symphony orchestras took leave of absence just to have an opportunity to play this amazing music in a full production.

She [Neidhardt] did not want a conventional Ring, nor did she want a self-consciously avant-garde production

In October 2001, three weeks after the Adelaide curtain fell on Parsifal, the creative team for the new Ring – set designer Michael Scott-Mitchell, lighting designer Nick Schlieper, costume designer Stephen Curtis, and Elke Neidhardt – began a week-long “retreat” in the Blue Mountains to discuss production concepts and designs.

Neidhardt was open to many ideas, but she had a few general guidelines. The story must be told clearly. Extremes were out. She did not want a conventional Ring, nor did she want a self-consciously avant-garde production, one that divorced action from meaning. “It’s terribly successful,” she said of the latter. “I don’t know why. I hate this stuff.”

Late in 2001, Neidhardt invited me to join the team as dramaturg. With such complicated works, stage directors don’t have enough time to do all the necessary research, and therefore rely on a dramaturg to “speak for the author”.

Let me share a couple of examples. For several weeks in 2002, Neidhardt and I corresponded about aspects of Siegfried, the trickiest of the Ring dramas to stage convincingly for a modern audience. I made the point that “it would be a mistake to imply that Wotan’s ultimate intention was to make possible the birth of Siegfried, for, in Die Walküre [the second drama in the cycle], it is Siegmund who is intended to be the saviour of the gods. Siegfried, by contrast, will be genuinely independent of his grandfather and doesn’t figure in his plans at all.” Neidhardt was surprised to hear this, but I was able to demonstrate its accuracy with references to Wagner’s actual text.

She asked about the Woodbird in Act II. Who was “manipulating” it? I explained that the voice of the Woodbird was that of nature caring for its own. In an earlier preparatory text, Siegfried exclaims that it was as if his mother was singing to him. So, it could be said that the Woodbird is also the voice of his mother’s (nature’s) love, warning her son of danger and leading him to Brünnhilde. Neidhardt replied that many German commentaries referred to the Woodbird as Wotan’s tool, “but your argumentation makes colossal sense”.

Götterdämmerung Prologue: Timothy Mussard as Siegfried and Lisa Gasteen as Brünnhilde. Photo: Sue Adler

As work on the Ring progressed, our attention turned to Götterdämmerung [the fourth drama] and to ways of depicting the hall of the Gibichungs. A few years earlier, I had visited Beijing and had been impressed by the Forbidden City. I suggested to Scott-Mitchell that because the Gibichungs existed in a different social and cultural world from the earlier characters of the Ring, the Forbidden City might offer a suitable inspiration. He liked this idea, and the result took the form of grand red lacquered arches that could be extended for the full depth of the stage, moved back to a halfway position, or stacked up against the rear wall like Chinese boxes, one inside the other. The resulting scene was unforgettable and highly dramatic.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

The 2004 production set a very high bar for the State Opera and it was enthralling for me to see it come to fruition. To my mind it was (and remains) the finest Ring to be staged in Australia and one of the finest anywhere.

A total of 20,260 seats were sold for the three cycles, and box office income totalled $5,727,000. Donations and sponsorships provided another $2,200,000, not counting government grants. It will remain a landmark in Australia’s operatic history and should make all South Australians, and the present opera company management, proud.

Peter Bassett (see full biography here) was dramaturg and artistic administrator for the 2004 Adelaide production of the Ring. For the 1998 Ring he had been a State Opera board member, and a member of the State Opera Ring Corporation Board, the Ring Lead-up Events Committee, and the Committees of the Friends of the State Opera and the Wagner Society of South Australia. More recently, he was president of the Wagner Society in Queensland from 2016-22 and organised symposia and talks for Opera Australia’s Ring in Brisbane in 2023. Bassett is the author of a number of opera publications, including ‘1813 Wagner & Verdi’, available to purchase here.

Peter Bassett (see full biography here) was dramaturg and artistic administrator for the 2004 Adelaide production of the Ring. For the 1998 Ring he had been a State Opera board member, and a member of the State Opera Ring Corporation Board, the Ring Lead-up Events Committee, and the Committees of the Friends of the State Opera and the Wagner Society of South Australia. More recently, he was president of the Wagner Society in Queensland from 2016-22 and organised symposia and talks for Opera Australia’s Ring in Brisbane in 2023. Bassett is the author of a number of opera publications, including ‘1813 Wagner & Verdi’, available to purchase here.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here