Today, we can predict the weather, although there is little we can do to alter its course or change its ultimate impact on our lives. The ferocity and destructive capacity of the climatic phenomena that animate the landscape still inspire awe and trepidation. Like our ancestors, we still run for cover as dark clouds coalesce and burst forth with torrential rains and howling winds which rattle our windows. We wait in anticipation for the crack of thunder after a bolt of lightning splits the sky.

In recent years, the severity and inconsistency of certain weather conditions and events has made us realise how vulnerable we are to subtle shifts in the world around us. Historically, the Japanese people recognised these forces and, through veneration, sought to propitiate them to avoid climatic and geologic upheaval.

These numinous forces are described as kami. Kami are anything that inspires awe or wonder in the natural world and can be applicable to towering trees and mountains or even ancestors. They are recognised and venerated in the context of the regionally specific ritual culture described in the English-speaking world as “Shinto”.

Children… are taught to fear them and to cover their belly buttons during storms to prevent their abdomens being consumed

For hundreds of years, the capricious and at times destructive forces that propel the winds and trigger thunder and lightning have prompted artistic expression. This pair of kami are known in Japanese as 風神Fūjin (wind), and 雷神Raijin (thunder) and they remain a pervasive presence in the cultural landscape of Japan.

According to ancient texts, Fūjin and Raijin were just two of the numerous offspring of the progenitors of the archipelago of Japan. They first emerged during the tempestuous 13th century in sculptural form as wrathful guardians at Buddhist temples and in handscrolls that depicted the origin stories of prominent shrines. In the 17th and 18th centuries they appeared on screens and sliding doors and later in woodblock prints.

During the 20th century they were co-opted by corporate Japan as mascots, becoming staples of anime, manga, and Pokémon – to the delight of children, who otherwise are taught to fear them and to cover their belly buttons during storms to prevent their abdomens being consumed.

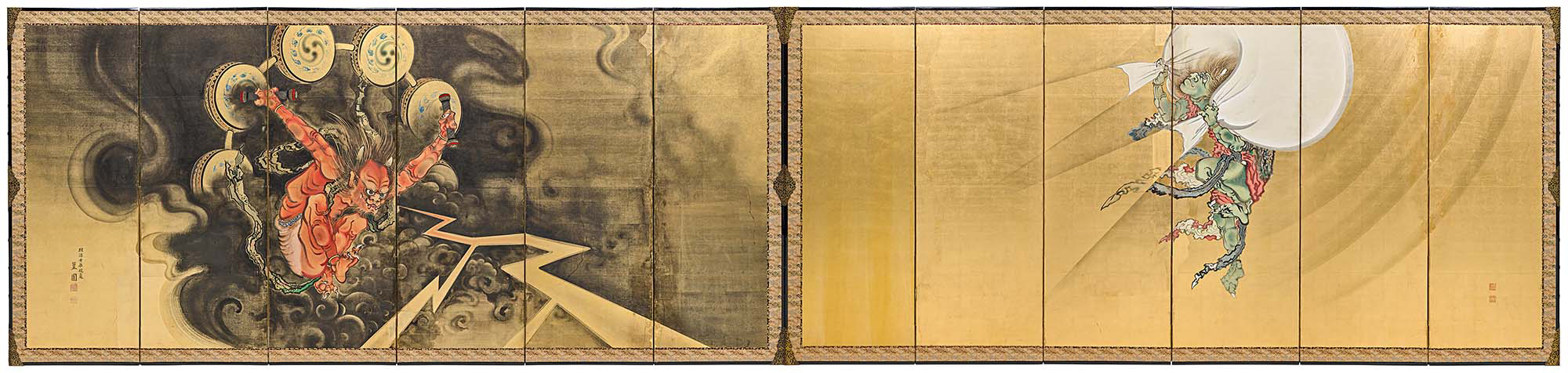

In 2022, the Art Gallery of South Australia acquired a pair of six-panel screens depicting Fūjin and Raijin, created in the summer of 1892 by the Kyoto-based artist Takaya Kōho. The screens depict the pair amid a field of gold as they summon the full force of their respective powers. On the right, Fūjin releases a tempest from his billowing white bag, while Raijin strikes a series of drums (taiko) to create the sound of thunder and cracks of lighting.

Takaya Kōho, Untitled, Wind God and Thunder God after Ogata Kōrin (1658-1716) and Tawara Sōtatsu (c1570-c1640) 1892, Kyoto, pair of six-panel screens; ink and pigments on gold and paper; MJM Carter AO Collection through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2022.

Takaya Kōho has captured the wild, untamed nature of the pair, depicting them in the “modern” style of late 19th-century woodblock prints. As a native of Kyoto, he would have been aware of previous renditions created by well-known masters of the Rinpa school Tawara Sōtatsu (d 1640) and Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716), as well as the earliest known representations on display in one of Kyoto’s most well-known temples, Sanjūsangendō.

The veneration of deities associated with the wind and thunder is not unique to Japan. According to some historians, Fūjin is a local manifestation of the deities that emanated from Central Asia along the Silk Road. Regionally specific manifestations appear in a Hindu context as Vayu and Varuna, and in Daoist beliefs as Fengshe and Leigong.

Fūjin and Raijin were likely transmitted from China to Japan during the 6th century as part of the Buddhist pantheon and first appeared in Buddhist sutras as demons attempting to frighten the historical Buddha. Their continued relevance is but a small example of the importance of the introduction of the sophisticated Buddhist practices and elaborate artistic culture that revolutionised many aspects of Japanese life and gave form to the numinous.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

They are but two of the vast number of kami that pervade the landscape of Japan. These beliefs reflect an intimate inter-relationship between nature, devotion and art, and ultimately represent the changing nature of humanity’s connection with the natural world. As we confront the dynamic ecological challenges and, at times, uncontrollable climatic conditions, it is important to remember the fragility and destructive capacity of the natural world and our need to find a harmony within it.

Takaya Kōho’s pair of six-panel screens depicting Fūjin and Raijin is on display in the exhibition Misty Mountain, Shining Moon: Japanese landscape envisioned, showing at the Art Gallery of South Australia until April 1, 2024.

Russell Kelty is curator, Asian art, at the Art Gallery of South Australia. This article is part of InReview’s Off the Wall series, in which AGSA curators offer an insight into specific works or displays at the gallery.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here