Film review: Escape from Pretoria

Film & TV

SA-filmed prison-break thriller Escape From Pretoria, starring Daniel Radcliffe, may have had a lucky escape itself by premiering on the small screen, writes Ari Mattes.

There is something undeniably appealing about prison escape films. Who doesn’t want to watch a bunch of underdogs band together and escape the clutches of their jailers?

We empathise with central characters whose imprisonment is usually unjust, if not illegal. We cringe, watching them tortured by cruel and psychopathic guards. We feel uplifted as we see – even in this context of absolute abasement – the fabled “human spirit” (whatever this thing is) able to soar above the misery of the situation and, through cunning and ingenuity, set the body free.

They are perfect examples, in other words, of the kind of cinematic escapist fodder that thankfully numbs our brains and bodies to the brutalities of reality.

Escape from Pretoria does its best to exploit both our disposition towards underdogs, and our historical knowledge of the barbarity of apartheid in South Africa.

Based on Tim Jenkin’s 2003 memoir Inside Out: Escape from Pretoria Central Prison, this is the first major feature film from UK-based director Francis Annan. Like so many low- to medium-budget films in the 21st century, it is a trans-national production, with the investment (and therefore risk) spread between Australia and the UK. Indeed, it was shot on location in Adelaide and surrounding suburbs, and looks like it.

A film about mechanics

Formally, the film is uninspired. There is nothing notable about its technical construction. This seems to be a perennial problem with so-called “true story” films, which often depend on the interest generated by this label at the expense of dramaturgy and aesthetic quality.

(This, of course, is not always the case – the true-story heist film American Animals was one of the most formally engaging films of 2018.)

What is interesting about Escape from Pretoria is the absolutely minor tenor of its narrative. It eschews melodrama and sentimentality, focusing on the mechanics of escape itself.

The film goes into great detail in its examination of the design and manufacturing of the tools and technologies Jenkin and his crew use to get free, including nine different wooden keys, and their testing under tense conditions.

In this sense, the film is procedural rather than character-driven. This suits the curious nature of the event on which it is based, and there is something refreshing about the narrative’s minimalist approach.

It doesn’t labour excessively to depict guards as disgusting demons, or prisoners as paragons of virtue. It doesn’t, in the style of American counter-cultural prison films like Cool Hand Luke and The Longest Yard, fetishise the eccentricities and idiosyncratic personas of different inmates.

Ex-wizard Daniel Radcliffe gives an earnest if forgettable performance as Jenkin, managing to pull off a pretty convincing accent and sweating and frowning in the right places. His fellow escapees are solid, especially Australian Mark Leonard Winter as Leonard Fontaine. Nathan Page, as the particularly unpleasant guard Mongo, endows the role with a quality of Eichmann-esque understatement that stops it from descending into super-villain caricature.

Disappointment at history

Yet, like so much post-apartheid media about apartheid-era South Africa, the film exists as a kind of channel for profound disappointment regarding the African National Congress’s post-apartheid rule.

This is realised in the film’s background echoes of faint nostalgia and in the painfully banal platitudes that end the film, posturing about freedom and democracy, the ANC and Nelson Mandela.

This kind of nostalgia is becoming increasingly difficult to stomach in a post-Marikana massacre context, in which the ANC were implicated in the lethal repression of protests about mine workers’ rights.

It seems that, in an age of increasing inequality in South Africa, the cultural spirit needs to return to the apartheid era to generate some semblance of hope about the future. In the era the film attempts to document, the name “ANC” was still synonymous with dreams of equality and a prosperous future for many South Africans.

In a current-day South Africa of growing inequality – captured in films set in the present (Necktie Youth) and future (District 9) – it is an easy strategy to return to the apartheid era to leverage the emotional investment of the viewer.

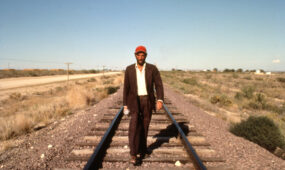

In any case, Escape from Pretoria offers an engaging diversion from news about coronavirus and police brutality. It’s the kind of minor, visually uninteresting film one senses would feel like a flop if projected onto a cinema-sized screen. It is better suited to the small screens with which we’re all currently forced to make do.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

Escape from Pretoria is now available in Australia through video on demand services.

Ari Mattes is a lecturer in Communications and Media at the University of Notre Dame Australia. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

![]()

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here