On that day in 2013 when plans were set in motion to create a theatre work using the songs of Bob Dylan, the planets were definitely in auspicious alignment. Because Girl From the North Country, which first opened in London in 2017, exceeds all expectations and seems to have created a new hybrid of music combined with theatre in the process.

Irish writer and director Conor McPherson was asked by the producers at Runaway Entertainment to write a four-sentence pitch, for a story and setting, to be delivered for Dylan’s approval. He described “a Depression-era boarding house in a US city in the 1930s with a loose family of thrown-together drifters, ne’er do wells, and poor romantics striving for love and understanding as they forage about in their deadbeat lives”. “We could,” he added, “have old lovers, young lovers, betrayers and idealists rubbing along against each other.”

The reply from His Bobness was almost immediate and unconditional. His trove of songs was at his disposal. Dylan’s office sent a parcel of 40 albums to help McPherson get started.

The result is a cluster of vivid portraits, a dream play of stories and songs set in Nick Laine’s heavily mortgaged lodging house in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1934. Times are uncertain and tough. The system has failed. Everyone is broke, out of work, or waiting on a miraculous financial bailout. Some are running scams, others plan to skip town to seek better prospects far away. Their destinies overlap and clash. Old loves are thwarted or found wanting, and new loves become springboards for change.

McPherson’s production, splendidly re-staged for this Australasian tour by associate director Kate Budgen, movement director Lucy Hind and resident director Corey McMahon, features Rae Smith’s décor – an old boarding house parlour in browns and murky browns with shabby furniture and peeling wallpaper. There is a long dining table for the guests, an old upright piano at one side, a curtained section for the lithe four-piece band (led by Andrew Ross) in the back corner, occasional flats lowered for external scenes, and a large screen for photographic projections of landscapes and archival photos.

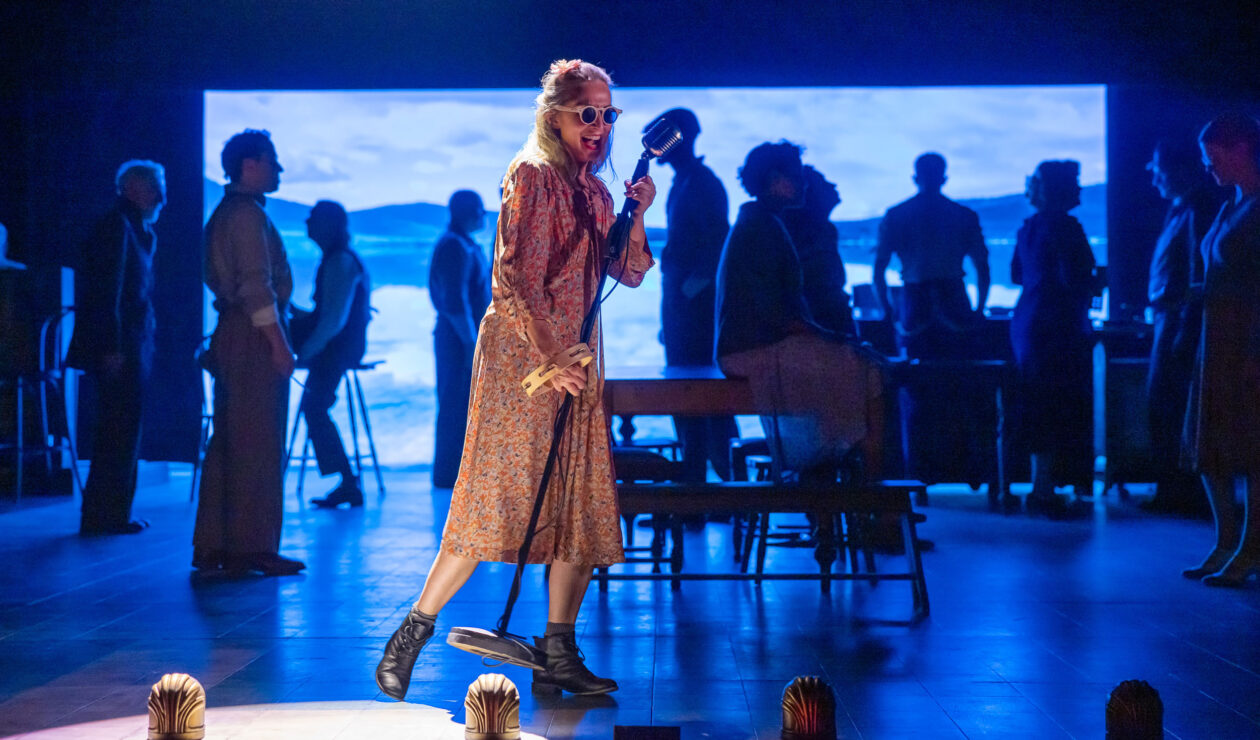

The stage is dim but the performers are bathed in the warm buttery tones of Mark Henderson’s lighting design, which highlights Smith’s homely ’30s costuming in blues, scarlets, belts, braces and fair isle, and uses startling shadow and profile silhouette effects for Hind’s swirling, soft-shoe shuffling choreography.

The sketchy but intense characterisations are galvanised by their uncannily apt connection to the Dylan songs McPherson has chosen. Long familiar favourites are used in unfamiliar and strikingly fresh ways. Interestingly, you might say paradoxically, he has mostly used bleak and fraying old-timey love songs, rather than Dylan’s famous overtly political anthems, to present and amplify the social justice and social realist themes in the text.

These are the plaintive heart-songs of forgotten and discarded people. It is a Depression musical version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, or Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood, or maybe The Grapes of Wrath – set in freezing Minnesota.

The performances are outstanding and often richly comic. Alongside the well-meaning but doomed Nick Laine, played commandingly (and at times with too many decibels) by Peter Kowitz, is Lisa McCune as his wife Elizabeth, only in her fifties but with early onset dementia.

McCune gives a wonderful rendering of McPherson’s brilliant creation. Often wearing stylish art deco sunglasses in contrast to her frumpy clothes, she moves among the action like a jester or a soothsayer, or a blind busker, linking the stories and giving other characters the candid benefit of her unfiltered mind. Like so many of the actors, her vocals are also first-rate, setting the situation with “Tight Connection to My Heart (Has Anybody Seen My Love?)” and, later, with the bluesy melancholy of her reading of “Like a Rolling Stone”.

Lisa McCune, Peter Carroll and Peter Kowitz in Girl From the North Country. Photo: Daniel Boud

Grant Piro is terrific as the bogus Reverend Marlowe, bringing sinister implications to the foreboding opening lines of “Slow Train Coming” and joined by the powerful singing of Elijah Williams as Joe Scott, a young African American boxer who has been wrongly accused and imprisoned for a violent crime.

Later, Williams makes “Hurricane”, Dylan’s ballad of another boxer wronged by false accusation, a riveting protest, interleaved with lines from the apocalyptic “All Along the Watchtower”. And, also a mark of McPherson’s wit and invention (and, of course, the brilliantly lyrical arrangements by Simon Hale), Williams sings “Idiot Wind” in a duet with (Nick and Elizabeth’s adopted black daughter) Marianne (strongly played by Chemon Theys), transforming Dylan’s irascible diatribe against media gossip into a chilling evocation of racism instead. The oddly macabre living tableau of the chorus preoccupied around the piano – contrasting the lonely duet – would have thrilled Meyerhold.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

There are many examples of sometimes minor Dylan songs taking on transformative depth and strength in this skilfully dramatic context. Helen Dallimore and Christine O’Neill, tremendous as Mrs Burke and Mrs Neilsen, deliver show-stopping renditions of “Sweetheart Like You” and (also from the Infidels album) “Jokerman”, which with six women singing harmonies around a broadcast microphone gives a new gendered emphasis to Dylan’s elusive lyrics.

Elsewhere, Elizabeth Hay (as Kate Draper) and James Smith (Gene Laine) sing a wistfully tender version of “I Want You” as they part ways forever. In another highlight, Blake Erickson, at one stage playing Elias, the mentally disturbed adult son of the Burkes, returns in a white tuxedo and a hot jive chorus line to make Dylan’s cheerily upbeat “Duquesne Whistle” into a ghostly locomotive apparition. Hay continues the destabilising impact with a stunning take on “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)”. Mention also must be made of pitch-perfect theatrical contributions by Peter Carroll as Mr Perry and Tony Cogin as Mr Burke.

Terence Crawford as the narrator Dr Walker. Photo: Daniel Boud

Conor McPherson, aided by his baritone narrator Dr Walker (played with Prairie Home Companion panache by Terence Crawford) has, like Sean O’Casey and Brian Friel, or Raymond Carver and Larry McMurtry, told us a bunch of captivating stories of hard times getting harder.

There are not the usual wish-fulfilment payoffs of a musical, but, instead, the tunes bring a tragic ballad-like stoicism and defiance to the drama. In this remarkable production, the almost mawkish “Forever Young” carries an inescapably wry irony and the full-cast closing gospel number from Saved is called “Pressing On”. Well, ain’t that the truth.

This production of Girl From The North Country – presented by GWB Entertainment, Damian Hewitt, State Theatre Company South Australia, Sydney Festival and Trafalgar Entertainment Group – is playing at Her Majesty’s Theatre until April 10.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here