For realist painter Tsering Hannaford, light is as important as life.

“Out the back, there’s a beautiful skylight,” she says, as we make our way to her studio which is tucked away in the garden of her West Hindmarsh home.

A blue, weathered door opens into a space flooded with natural light, even on a rainy, overcast afternoon.

“I really love working with the natural light – nothing compares,” Hannaford says.

The brightness of the studio is heightened by the white walls, while rustic brick pavers make it feel as if there’s no line between indoors and outdoors. Large windows welcome in the greenery of the garden.

“You get to work with the rhythms of nature as well, like the seasons,” the artist says, motioning out to the yard. “The time of year really dictates how long I work. In summer, I’ll go to seven. In winter, it’s 4.30, so it [winter] is a good time to go to Europe and get some art inspiration.”

Tsering Hannaford loves working with natural light. Photo: Jack Fenby

The studio also has a cosy feel: there’s an indoor plant, a chaise lounge, a fireplace, and a few pieces in progress – including paintings of clam shells and landscapes that are a response to a residency she did two years ago with Paspaley Pearl Company in the Kimberley. This space is where Tsering does her still-life work, and the occasional portrait. The others are done in the spare room at the front of the house, an insight into how portable portraiture can be.

“I will take the mattress and bed in and out when I need to paint in there,” she says.

“I really just need a room with a window. I bring in my canvas, bring in my easel, my plinth and painting supplies, and I can make any space a studio, really.”

But the studio that sits out the back, the one with the beautiful skylight, has another layer of significance – it was built by Hannaford’s father, Robert, a renowned and widely celebrated realist artist who has been a finalist in the prestigious Archibald Prize 27 times over his career.

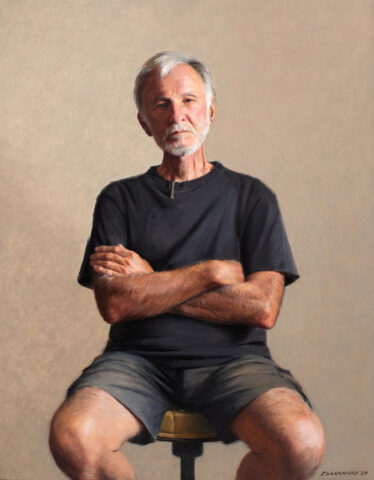

Archibald Prize 2024 finalist Tsering Hannaford’s Meditation on seeing (portrait of Dad), oil on board, 117.2 x 91cm, © the artist. Photo: Art Gallery of NSW / Jenni Carter

This year, Robert was the subject of Tsering’s own Archibald Prize portrait, Meditation on seeing (portrait of Dad), which was shortlisted for the award and is currently on show in the exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW.

“It was my 10th year [as a finalist] this year, which was amazing,” she says. “I think round numbers, like a decade, really make you reflect.

“My dad has really been my biggest cheerleader and mentor, my inspiration throughout the years, so to honour him, I felt in this particular year, it’s really significant.”

Over 12 sittings with her father, Hannaford says she had the opportunity to reflect not only on their relationship, but also on her practice – two things which are inextricably intertwined.

“I really just wanted to reflect on the essence of what painting is for Dad and also for myself, which is seeing and seeing clearly.

“A big part of the painting process is entering into what you could call a flow state of mind. When you’re working in that way, the sum of all of your knowledge of anatomy, perspective, tone, colour, it all comes into play in the moment, as if it’s all in flow.

“That’s when you capture something really special about your subject, and that’s the biggest teaching that my dad has imparted on me.”

Tsering with some of the works-in-progress in her studio. Photo: Jack Fenby

Growing up, Tsering Hannaford lived and breathed art.

“There were definitely boundaries,” she says, laughing. “When I was a young child, there was a line in the studio that my dad drew on the floor that I couldn’t go past.”

That boundary disintegrated as Hannaford grew up.

“We’d have my dad’s subjects over to the house all the time,” she says, naming former Australian prime minister Paul Keating as an example. “As a child, I didn’t realise how quite how important they were!

“The studio was always open, always accessible. I could always go knock on the door and ask for something, and Dad would always put the brushes down and give me his attention.

“I feel like it was unavoidable that I do something creative as well.”

Despite this, for a long time Hannaford pushed back against art as a career path.

“I definitely did not want to be an artist,” she says. “When I was younger, my art teacher had to convince me to take it as my Year 12 subject because I didn’t want to.”

The artist is always trying to improve her skills. Photo: Jack Fenby

After going on to major in psychology at university, it was a trip to Europe in her gap year that drew Hannaford back to her roots.

“I was really inspired by the art,” she says.

“I always had it in me. When I was stressed at uni, I’d just be drawing and that would be my way to switch off. So it was something that was always there.”

Knowing that her area of interest was realism, Hannaford undertook speciality training in classical methods in New York, at the Grand Central Atelier and Art Students’ League, and at Studio Escalier in France.

In the decade since, her work has been hung in some of the nation’s most celebrated prizes, including the Portia Geach Memorial Award and the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, as well as the Archibald.

Hannaford is also an advocate for the arts and sits on the board of Guildhouse, saying the organisation was “incredibly supportive” of her career, especially in the early days.

“It’s such a beautiful, warm community – so supportive, doing vital work for the arts, advocating for artists. To be 10 years in now, and giving back at the board level is so significant to me. It means so much.”

Tsering Hannaford sees portraiture as a way to tell people’s stories. Photo: Jack Fenby

At this stage of her career, Hannaford knows how to nurture and articulate the three pillars of her own practice that keep her satisfied.

“My work is predominantly values-based, led by some pretty strong ideas about doing excellent work, being the best at my craft, to the best of my ability,” she says. “I’m always trying to improve and hone my skills in my chosen area.”

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

Second to that, Hannaford says her work is about connection – a connection that takes 15 to 20 hours, over seven sittings, to establish with each and every one of her subjects.

“By the end of the process, we’ve talked about everything from life to work to aspirations. I feel sometimes like I have a new friend and I feel like the subjects often feel really, really seen.

“Portraiture really resonates with me because I love telling people’s stories in in a quiet way. I feel like I can convey the essence of my subject through my painting.”

Thirdly, Hannaford uses her practice as a means of self-expression.

“Through my self-portrait work in particular, I’ve examined my experiences as a young woman growing up in the world that we live in,” she says.

Sanctuary: Inside Tsering Hannaford’s inviting studio. Photo: Jack Fenby

For Hannaford, painting from life – whether it be still life, her life or that of someone else – allows for evolution and collaboration. It means working with faces, seasons and light; ultimately, it means working with impermanence, to create something permanent.

“Painting is intimate, and it is personal. In the end, we end up with a memory of the experience which is physical: the portrait itself.”

In the Studio is a regular series presented by InReview in partnership with not-for-profit organisation Guildhouse (see previous stories here).

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here