ABOUT TABOO

Taboo is Kim Scott’s most recent novel, and the third to be set in the Wirlomin Noongar Country of his heritage, stretching roughly from Albany to Esperance along the southern coast of Western Australia.

The novel is centred upon the opening of a Peace Park, near the fictional Kepalup, to commemorate a local massacre site. Tracking over old scars brings both pain and a renewed sense of belonging for a community galvanised to rise again from the ashes of the past.

At this community’s heart is Scott’s protagonist, Tilly, a teenage student with a troubled family life who is coming to terms with her own Noongar heritage. She must confront spectres from the near and distant past while navigating the fault lines of history and community before true healing can begin.

Taboo was inspired by the development and opening of the Kukenarup Memorial in 2015, near the township of Ravensthorpe. These events are a reminder that Scott’s novels, although works of fiction, are always returning to deeply personal terrain.

It is this personal engagement with land, past and heritage that give Scott’s works their unique power and poignancy. They are stories that can reshape and recalibrate understandings of a whitewashed history, while singing the song of place.

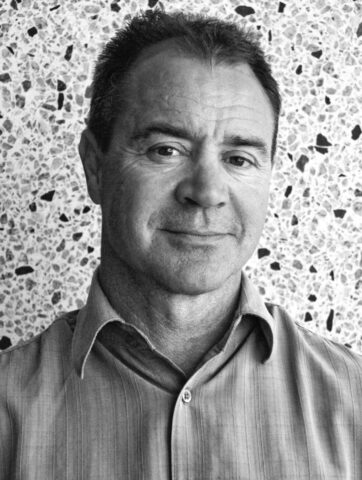

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Photo: Fremantle Press, 2023

Born in Perth in 1957, Scott began writing while working as a secondary school teacher. While teaching at an Aboriginal community in the Kimberley he also began researching his own family history, a process that would culminate in his first novel, True Country. Subsequently, Scott became the first Indigenous author to win the Miles Franklin Literary Award for Benang in 1999, and the first Indigenous writer to win the award twice with That Deadman Dance in 2011.

Scott’s literary endeavours have long been paired with efforts towards community and cultural revival in the region he is from, with The Wirlomin Language Project at the centre of these efforts. He was West Australian of the Year in 2012 and is currently a Professor of Writing at Curtin University.

QUOTES FROM THE AUTHOR

“I’m speaking from a very regional perspective here. It seems to me that any ‘global discourse’ has strong homogenising tendencies, and therefore we need to strengthen regional voices so they remain true to their own imperatives at the same time as being empowered to enter into exchange and dialogue.” – ‘Covered up with Sand’, 2007

“My work with community language groups is a way of being a ‘literary man’ in a community context. Not just posturing. And the so-called high literary stuff or whatever it is, is both very private and … speaking to a wider circle, an imagined community out there.” – ‘Those Old Songs of Place: A Conversation with Kim Scott’, 2017

“This is an Aboriginal nation, you know; it’s black country, the continent… There’s a need for continuing cross-cultural exchange, I think, for negotiation, and the reconciling to history – our different parts in it. How to be and live on this, the oldest continent on earth, where some of us who are descendants of the people who first created human society here are, by and large, at the bottom of the heap, collectively…” – ‘Kim Scott talks to Anne Brewster’, 2012.

Sunrise overlooking Wellstead Estuary, with West Mount Barren in the distance. Photo: Samuel Cox, 2021

QUESTIONS AND DISCUSSION POINTS

Scott has spoken of writing from a very regional perspective. How does this manifest itself in Taboo? How does this regional focus create a story that might be relevant to other times and places?

Scott’s fiction, including Taboo, has been associated with magical realism, a term linked with Latin American authors from the Global South, yet also one criticised by a number of Indigenous writers including Scott himself. Why might this term be problematic and do you think Taboo justifies its use? Can you think of any alternatives?

Many of Taboo’s characters are marked by the lingering intergenerational effects of colonialism and government policies. How do the characters confront these?

Despite being heavily involved in the Wirlomin Language Project, Scott largely avoids using Wirlomin Noongar language in Taboo. Why might he choose to do this?

What do novels and stories from Aboriginal Australia offer us that other Australian fiction does not? Has the novel altered your perception of Australian history?

FURTHER RESOURCES

- An essay by Scott on both the problems of calling Australia ‘postcolonial’ and the possibilities of reconnecting with regional Indigenous perspectives and heritage.

- The Wirlomin Language Project

- A recent Kim Scott lecture, ‘NOT JUST WARRIORS OR VICTIMS’.

TAKE TO THE PAGE: CREATIVE WRITING PROMPTS

“‘Words, see. It’s language brings things properly alive. Got power of their own, words. Some more than others.’” — Taboo (pages 98-99)

Make a list of adjectives and phrases describing the place you live, or the place you are from (this might be a region, a town, a city). You might consider the physical appearance and qualities of the place, its inhabitants, the ecosystems in which it exists, and/or its history and stories.

*

“Our hometown was a massacre place. People called it taboo.” —Taboo (page 1)

Now consider the existing name or names of the place you’ve chosen. If you were re-naming the place based on your list above, what might you call it? For example, Adelaide/Tarntanyangga is often called The City of Churches. Create a second list of possible names.

*

“One may as well begin, ‘Once upon a time’… Except this is no fairy tale, it is drawn from real life.” — Taboo (page 8)

Begin a story set in your chosen place using a ‘name’ from your second list, as well as the phrase ‘Once upon a time’. For example, Once upon a time in The City of Churches…

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

*

If you’re interested in sharing your work, please come and find Stories from the South on Facebook, and look for our “Creative Writing” thread.

MORE STORIES FROM THE SOUTH

If you enjoyed Taboo, why not also try one of these books or poems?

- Jack Davis, No Sugar (1985): An acclaimed play by a trailblazing Noongar poet and playwright that looks back to the depression era to depict a family’s struggle against government policies of assimilation and forced removal.

- Natalie Harkin, Archival-Poetics (2019): after years spent working in South Australian archives on Aboriginal people, Harkin not only writes back to the archive, but creates a poetic work that becomes an archive of its own.

Or other books by Kim Scott, such as:

- Benang (1999) and That Deadman Dance (2011): Kim Scott’s Miles Franklin Award-winning novels, both of which are set along the south coast of Western Australia.

- True Country (1993): A schoolteacher’s life is transformed by the experiences he has at a remote community in the Kimberley.

- Kayang and Me (2005): Scott and his elder, Hazel Brown, share stories that intertwine to tell a history of the Wirlomin Noongar people.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here