Jane Austen’s surviving letters make intriguing reading. It is easy (and not uncommon) to lift passing remarks and quote them as evidence for all kinds of biographical details. It has been proposed, for example, that Austen disliked music.

In May 1801, when Austen had just moved to Bath with her parents, she met Mrs and Miss Holder, mother and daughter. She wrote to her sister Cassandra, ‘It is the fashion to think them both very detestable, but they are so civil, & their gowns look so white & so nice … that I cannot utterly abhor them, especially as Miss Holder owns that she has no taste for Music’.

On the other hand, in August 1805 she described meeting a Miss Hatton, who had ‘little to say for herself. … Her eloquence lies in her fingers; they were most fluidly harmonious’.

How can we reconcile these two opinions: seeming to approve of one woman for being unmusical, and another for being musical?

Six years later she wrote to Cassandra of a Miss Harding: ‘an elegant, pleasing, pretty looking girl, about 19 I suppose, or 19 & ½, or 19 & ¼, with flowers in her head, and Music at her fingers ends. – She plays very well indeed. I have seldom heard anybody with more pleasure’. This is the remark of a music-lover. How does it tally with her description in 1813 of [someone] she liked ‘for being in a hurry to have the Concert over & get away’?

Author Gillian Dooley playing at Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton. Supplied image

It might not be possible to explain away all these contradictions. The best chance we have is to take them in the context of the rest of the correspondence, of the surviving memoirs, of her novels and other writings, and, above all, of her music collection.

Why does it matter whether or not she liked music? After all, Austen’s fame is not as a composer of music but as a composer of narratives. She was not even writing poetry, which is arguably more allied to musical forms than prose. Why is it important that she was an amateur musician who spent some of her leisure hours playing the piano and singing music much of which, unlike her own works, is almost completely forgotten today? It was just a hobby, after all, one might argue. She was not a professional musician, only an amateur.

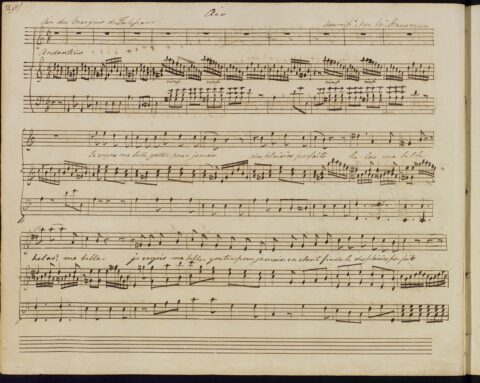

One of Jane Austen’s manuscripts: Air from the Marquis de Tulipano by Giovanni Paisiello. Image courtesy Jane Austen’s House Museum

In my book, I offer several possible answers to this question. One reason is that her musical practice provides background for the music that appears as part of the lives of the characters in her novels. Knowing about music in Austen’s own life helps readers understand her characters’ cultural and social milieu – what would be expected of a young musician in a domestic setting, providing entertainment for family and friends and meaningful occupation for her leisure time.

Another is the light Austen’s musical knowledge throws on her familiarity with political and social currents, such as the war with France, the national importance of the Navy, and the relative popularity of British music and music from continental Europe. More broadly, it provides a detailed example to music historians of the place of music in the life of a woman of Austen’s generation and class in England.

However, for me, the most important reason to explore the music in Austen’s life is the rhetorical link between writing and making music, especially given the musicality of her prose.

Her knowledge of the theatre has been explored by several scholars, and it is no accident that many of the pieces of music in her collection had their origin in theatrical productions of some kind. But all music expresses and explores a range of emotions and subjective states of mind, sometimes beyond the capacity of written language, often adding depth and meaning to lyrics that are in themselves unremarkable.

The surviving collection of music that belonged to her shows that Austen would have been a reasonably accomplished pianist and singer, and, along with other sources, shows that she sustained her musical practice throughout her life.

The relationship that a practising musician has with music in general is not usually a simple one. As with any field of knowledge and expertise, the more a musician knows about music, the more discriminating she is likely to be. She will develop her own tastes in repertoire. She will favour music in some settings over others.

In a letter from Bath of 2 June 1799, Austen wrote to her sister that she and her companions were going to attend the King’s birthday gala in Sydney Gardens on 4 June: ‘I look forward with pleasure, & even the Concert will have more than its’ (sic) usual charm with me, as the Gardens are large enough to get pretty well beyond the reach of its sound’.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

I take this as the statement of a musical woman who prefers to have a choice about whether to listen to a particular piece of music or a particular performance in a particular time or place.

Few musicians in my experience enjoy loud music in restaurants, or piped music in supermarkets. They like to enjoy music on their own terms, and to be able to choose when and where they experience it.

As for Austen’s own musical taste, I conclude that although the evidence is somewhat mixed, it appears that overall Austen personally favoured songs that were musically less complex and virtuosic and that allowed the singer to convey the meaning of the words more directly to her audience.

This is an edited extract from She played and sang by Gillian Dooley, an Honorary Associate Professor in English at Flinders University.

The work reveals a previously unknown part of Jane Austen’s world by delving into the relatively recent digitisation of music books from Austen’s immediate family circle.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here