Nel Law is one of those ground-breaking Australian women you’ve probably never heard of. Rachael Mead hadn’t heard of Nel either, until she was reading a book about artists’ responses to Antarctica and found herself captivated by a particular image of an abstract painting.

“It’s this brilliant emerald green colour and it’s of the face of an iceberg with these little rows of penguins, sort of like morse code, dotted along the ledges – it’s really beautiful,” says the novelist and poet.

“I was looking at this gorgeous painting on a colour plate and down the bottom it said ‘Nel Law’… I’d never heard of her but it sparked my curiosity.”

That was around 2018 and at the time there were only a couple of sentences about Nel on Wikipedia, describing the Melbourne-based artist and poet as the wife of scientist and explorer Phillip Law and the first Australian woman to visit Antarctica.

In fact, as Mead soon discovered, Nel had stowed away on the icebreaker Magga Dan during a 1961 expedition to the frozen continent led by her husband, who was director of Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) from 1949-66. Australian women were not allowed on ANARE expeditions until 1976, but Nel had hidden in Phillip’s cabin until the ship left port. During the months-long voyage, she painted more than 100 oils and watercolours.

“The fact that I had never heard of her, having thought I was pretty well-read on the subject of Antarctica, and then the whole stowing-away thing – I thought, there’s got to be a story here,” Mead says.

Author Rachael Mead. Photo: supplied

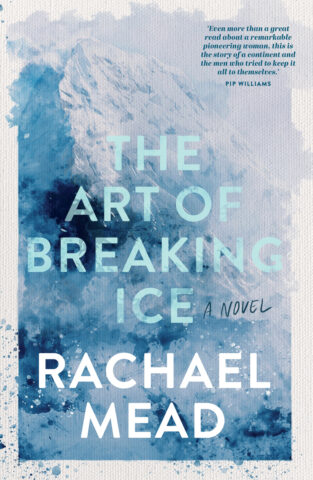

In her historical novel, The Art of Breaking Ice, published this week by Affirm Press, she takes the bones of the true story and uses artistic licence to weave a colourful fictional account of Nel’s adventures and challenges on the Antarctic expedition.

The subject matter is a significant departure from Mead’s previous novel, The Application of Pressure, which followed the experiences of two Adelaide paramedics, but it is familiar territory for the writer, who has long been fascinated with Antarctica and has visited it twice herself. The first time was in 2005, when she got to spend two weeks at New Zealand’s Scott Base while studying for a post-graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies at the University of Canterbury. Later, in 2013, she travelled on a tourist ship along the West Antarctic Peninsula and to the island of South Georgia.

While this first-hand experience has helped her envelop readers in the unique landscape and atmosphere of Antarctica – including the extreme weather and often claustrophobic conditions of the ship and bases – Mead has also drawn extensively on Nel Law’s diaries, which are now held in the National Library.

“I found them fascinating, and you can tell that she was an artist because they’re very descriptive about the different landscapes she was seeing and her responses to seeing ice and snow… you could see that she was just drinking in the landscape visually,” she says, adding that she also borrowed from Nel’s descriptive language.

“Being such a creative person, she’s actually a very good writer. She was so focused on the visual aspect of Antarctica… she describes icebergs as chaste, which is really interesting, so that’s in the book. She also went up in a helicopter and she was terrified of heights… that’s in the diary, too.”

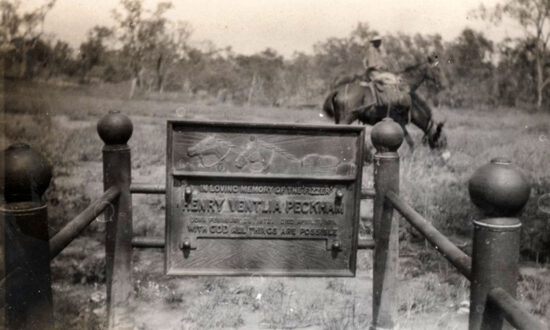

Nel Law at work on the ice. Photo courtesy Australian Antarctic Division

In the beginning, Mead found the story almost wrote itself: there was the 1960s artist, teacher and housewife defying gender norms, and the obvious excitement surrounding Nel stowing away on board the ship – which in real life created controversy from the outset after a journalist started asking questions even before the Magga Dan embarked on its journey.

But then the author noticed there were many gaps in the diaries, which gave little hint of any tension or challenges during the expedition. She says she was reminded of when she kept her first diary as a young girl and her brother broke its tiny lock and teased her about the contents.

“I learnt very quickly that nothing is private, so it became just a record of what I did and what I saw. I thought, oh my goodness, she’s doing exactly the same thing. There’s very little [in the diaries] about what it’s like to be a woman alone with a whole ship full of men; there’s very little about the male gaze and being under intense scrutiny all the time.”

In The Art of Breaking Ice, Mead invents several characters to help fill those gaps and drive the narrative, imagining how the scientists and crew members might have responded to Nel as the only woman on a ship with nearly 70 men – and the boss’s wife, to boot. While she acknowledges that available evidence suggests the Laws had a close and supportive marriage, the story also explores how living and working in such close quarters may have impacted the couple’s relationship.

“I can imagine, with Phil being in a position of such responsibility and working all the time, the level of stress,” Mead says, reflecting on the dynamic on the 1961 expedition. “People show different sides of themselves in work environments and under stress, so it would have been very interesting for her to see, as his wife, his work persona. I’m sure there would have been quite a considerable contrast to how he was at home.”

She adds: “It [the novel] is based on real events but it is still a work of imagination; a lot of creative liberties have been taken.”

Another noteworthy aspect of The Art of Breaking Ice is that it explicitly references the fictional Nel’s symptoms of peri-menopause, which is rare even in contemporary fiction. Mead admits she had to be wary of narratives buying into tropes about menopausal women, but says she was adamant she wanted to break the “ridiculous” silence surrounding the topic.

A video (above) from the National Archives showing Nel Law and ANARE scientists.

ANARE was concerned about the potential fallout from Nel Law’s journey to Antarctica, to the point that it sent a directive dictating what she was to say to the media on her return. Ultimately, however, the story fuelled interest in the continent and Australia’s activities there, although it was another 13 years before the nation’s policy on sending women to Antarctica changed.

Nel, who spent lengthy periods at home alone while Phillip was away in Antarctica, founded an organisation in 1965 to support the wives of expeditioners (today it has become the Antarctic Family and Friends Association), and was also the founder and inaugural president of the ANARE Club.

She had her first solo exhibition in 1964, and today the Australian Antarctic Division has some of her artworks in its Special Collections. The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery also has a number of paintings, including one of Mead’s favourites: a watercolour of a beach on Macquarie Island packed with thousands of penguins. The ashes of both Nel, who died in 1990, and Phillip, who died in 2010, are interred at Mawson Station.

Artist Nel Law during the expedition. Photo courtesy Australian Antarctic Division

Asked to name one of her most surprising discoveries about this unsung artist and adventurer, Mead says Nel’s diaries reveal she was “unabashedly girly” even in the most male-dominated environment.

“She took several bottles of perfume down there. The bits [in the novel] with her taking brightly coloured scarfs and dressing for dinner are true: she wanted to add a splash of colour to their evenings. She didn’t want to be one of the boys at all… She used a full face of make-up every day but was also very conscious of using the make-up as sunblock as well.

Get InReview in your inbox – free each Saturday. Local arts and culture – covered.

Thanks for signing up to the InReview newsletter.

“She hated the bulkiness of the clothes and how long it took to get dressed and still at the end of it be so fundamentally unattractive, which was quite funny.”

Reading these things, Mead admits she could feel her eyes rolling. Ultimately, however, she found herself inspired by Nel Law’s courage in defying expectations and gender stereotypes, and she hopes others will be similarly affected.

“I did have an enormous amount of respect for her by the end of it.”

The Art of Breaking Ice, by Rachael Mead, is published by Affirm Press and available now. In addition to her debut novel, The Application of Pressure, Mead has published four collections of poetry. She is also a reviewer for InReview.

Support local arts journalism

Your support will help us continue the important work of InReview in publishing free professional journalism that celebrates, interrogates and amplifies arts and culture in South Australia.

Donate Here